Making OPAQUE Clear.

Published 20 October 2024 at Yours, Kewbish. 4,807 words. Subscribe via RSS.

Introduction

I am not a cryptographer. I’ve participated in enough CTFs to have had the refrain “never roll your own crypto” drilled into my head. Leave the group-modulo-n wrangling to the professionals, as the undertone went. While I won’t encourage you to do so, today I’ll give you enough of the basics to implement your own key exchange protocol. I’ll leave the deploying it to prod to you.

To build up some backstory: I recently met someone, who, when I asked to exchange contacts, told me to add them on Signal, instead of Discord or Whatsapp. This was new. A few years earlier, I’d had the same reaction when I needed to join some group chats that were hosted on Telegram1. I’ve just finished a book about Tor for a reading group, and attended a couple talks about mixnets. While it might have something to do with the fact that my office is in the Cybercrime Centre, recent news like the arrest of the Telegram founder and the viral AR I-XRAY glasses have been bringing up topics around privacy and security.

To me, a core thread running through these concerns is the question of who we can trust with our data. There are growing movements to abandon big-tech platforms and use dumb phones without internet. Folks hop between the secure messaging platforms de jour, or at least onto the incumbent, which appears to be Signal. Signal, Protonmail, even something as familiar as Whatsapp: they’re all end-to-end encrypted. This means the servers that run these platforms only store encrypted copies of your data, and the only people who can read your funnier-in-your-head texts are you and the intended recipient. This encryption usually uses big random numbers instead of passwords, since passwords are lower-entropy. These platforms also (usually) won’t store your keys for you, since that’d undermine the whole point of end-to-end encryption. You’re therefore the only person in the world who can correctly decrypt any messages that are sent — nice and safe. But what happens when you lose your phone? Sure, the app prompted you to save a recovery file, store a twelve-word recovery phrase, or back up your keys somewhere before proceeding, but like most folks, you’d probably just skipped past that step.

Let’s use passwords, you say — folks know how to use them, they generally do a better job at recording them somewhere, and there are password manager tools readily available so it’s rare you’ll forget them. However, even besides the myriad misconceptions about strong passwords and the dangers of people reusing passwords, there’s the fundamental problem that the platform’s server will have to store your password. Nowadays, it’s usually stored hashed, so that’s mostly fine — should someone break into the service’s database, their only choice is to brute-force or rainbow-table their way to steal your original password.

Now consider what happens in between you hitting ‘Log in’ on the auth page and the server processing your password — or more precisely, how the bytes of your password are transmitted. Yes, hopefully in this day and age it goes through TLS, so no one should be able to read it. But the core problem is that it’s still in plaintext. Once the server receives your password via HTTP, it still needs to read and process it into a hash, to compare against the stored hash. And how is this processing done? In plaintext. That puts a lot of trust on the server to behave honestly. Even if the server behaves as expected, the hardware it runs on might be vulnerable to attacks: because the password is transmitted in plaintext, it’s also in the RAM and cache in plain text. When I was at Cloudflare, I learned about some of the ways the team architected the Workers platform explicitly for better isolation on all levels, guarding against speculative execution bugs, for example. If the server’s using plain passwords, it’s vulnerable to SPECTRE and other lower-level attacks like it.

It seems, then, that there’s no safe option. Either you have better security at the risk of fallible users losing access to their data, or you get a more familiar user experience at the expense of many layers of security concerns. However, there’s a way to augment passwords with some neat cryptography so that you can effectively get the best of both worlds. Enter OPAQUE: a password-based key exchange protocol that lets the end user input a password and save their keys on the server, while not allowing the server any access to the password. It retains the server-has-zero-knowledge properties that we’d expect in an E2E setting and requires both user and server to participate in any login attempts, reducing the feasibility of brute-force attacks. OPAQUE was selected for standardization by the IETF over several other similar password-based protocols, including the other top contender SRP-6a, because of this defense against brute-force attacks. It’s also been implemented by several companies, including Cloudflare and Facebook.

In my current research internship, I’ve been working with variants of OPAQUE as applied to key recovery for E2E services. We’re figuring out how to adapt OPAQUE to store and retrieve a user’s private key via a password: for example, in cases where they’ve lost access to their old devices. We needed OPAQUE’s properties: we don’t want the server to be able to reconstruct the password and read the user’s keys, nor do we want the user to keep the only copy of keys locally and end up susceptible to brute-force if any encrypted info leaks. We’re adding some other goodies on top, too, but I had to implement a vanilla version first. When I was doing so, I had to trawl through tens of pages of dense crypto papers and cross reference the OPAQUE spec with the myriad example repos, but I think the core ideas boil down much more intuitively.

Protocols like OPAQUE shouldn’t be secure-by-obscurity, and certainly not secure-by-lack-of-good-high-level-public-explanations. This post aims to give you the walkthrough of OPAQUE I wish I had when I embarked on this project. I’ll assume some general CS knowledge, but otherwise I’ll provide the context you need if you’re starting from scratch. I’ve chosen to gloss over some of the related crypto concepts to focus on just what’s needed to understand the OPAQUE exchange, but I’ve included links and mentioned other keywords if you’d like to dive deeper.

I hope this post will serve to make OPAQUE clear and you less wary about crypto — reams of LaTeX can be scary, but I promise this won’t be.

Background: Elliptic Curves

One of the concepts I’ll assume some background in is public-key cryptography. The basic idea is that you store two keys: one public and one private. You share your public key with others, and keep your private key to yourself, as the names may suggest. To encrypt something, you take your private key and the public key of the intended recipient together and do some operations on it, which ensures that only the recipient can decrypt your message, since only they have the private key associated with their public key. The idea is that public keys are derived from private keys using some hard-to-reverse operation, and that you can easily derive the public key from the private key, but not vice versa. For example, multiplying numbers is easy, but factoring numbers is hard, so part of what underlies the RSA cryptosystem is that you can’t easily factor numbers to derive the secrets that are used to create the private key2.

Elliptic-curve cryptography works on the same principle. The hard-to-reverse operation here is multiplying a point on the curve with a number. Let’s build up to multiplying with points on the curve by first adding a point to itself, which we can then repeat n times to get multiplication by n.

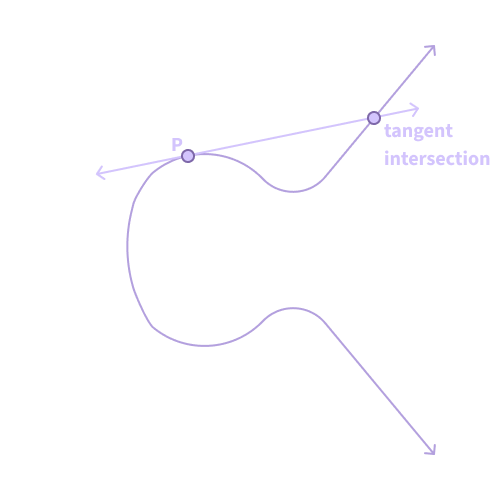

We first have to start with the given point on the curve. The formula of this curve will change depending on the particular curve you use (and there are plenty), so I won’t go into detail about it now. Pick a point P. To add the point to itself, you’ll need to draw the tangent line to the curve at P — this is the line that follows the shape of the curve at point P. Extend the tangent line far enough, and you’ll find that it intersects exactly one point on the curve. Call this point the tangent line intersection.

Figure 1. Drawing the tangent line to P.

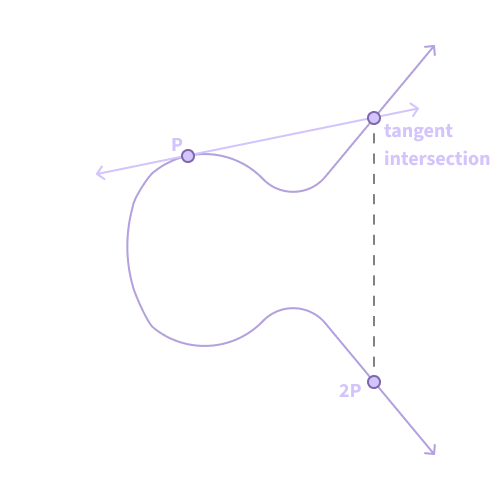

This tangent line intersection point is then reflected in the x-axis to get the doubled point, 2P.

Figure 2. Reflecting across the x-axis to get 2P.

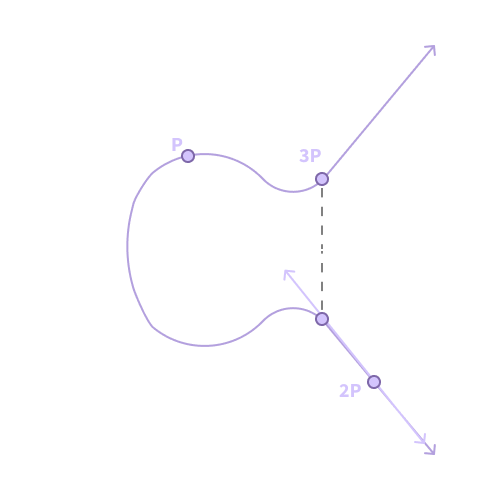

We can then repeat this again, with the tangent line for the point 2P, to get 3P, and so on. There are several optimizations to do this multiplication faster, including the double-and-add algorithm.

Figure 3. Repeating to find 3P.

The private key in elliptic curve cryptography is the choice of a number n, and the public key is the curve’s basepoint multiplied by n. The curve’s basepoint is a point that’s defined along with the curve (technically, the generator of the group we’ll be operating in) — just consider it as a constant that’s handed to you together with the definition of the curve. It’s easy to compute the public key given the private key, since the multiplications aren’t hard. However, if you want to recover the private key given just the resulting public key point, you’ll have to try every single possible value of n, which is assumed to be infeasible. This multiplication is called the elliptic curve discrete log problem, as an analogy to the discrete log problem of finding the number x such that g^x = y for some public number y.

One thing to note is that if you know the number n that you multiplied by, it’s easy to ‘undo’ a multiplication as well. You can multiply by its inverse — think of it like doing n * P * 1/n — to recover just your original point. You might wonder why we can’t do something similar to recover the number n from our public point, since the curve’s basepoint is a public parameter. However, you can’t analogously ‘invert’ a point, so you’ll still have to end up trying all the possible values of n. The core takeaway of all this is that division by a number is easy, and division by a point to get the number back is hard.

Metam-OPRF-asis

Let’s put that elliptic curve theory to work, starting with the main building block of OPAQUE: the oblivious pseudo-random function (OPRF). We can build up what an OPRF is step by step:

- A function is a mapping from a domain of inputs to a range of outputs.

- A random function is an entirely random mapping from inputs to outputs. This means the random outputs should be uniformly distributed, which means there’s no obvious bias in the outputs.

- A pseudo-random function looks like it’s an entirely random mapping, but is actually deterministically mapping inputs to outputs. It’s very important that it looks like a random function, so it also needs to have a uniform distribution of outputs.

- An oblivious pseudo-random function is a random function that requires two people to evaluate, where neither person learns what the other put in — they’re oblivious to the other party’s input.

More concretely, let’s describe the two people as a client and a server and define an OPRF as a function F(server_input, client_input) such that the client never learns the server input, and the server never learns the client input nor even the final result of the function. I think Wikipedia and other resources do a terrible job of explaining how this is possible, because intuitively, it isn’t. How can the server, who’s evaluating the function, not know its own output? How can the server also not know the client’s input, if it was required as part of the function’s inputs in the first place?

The answer lies in the elliptic-curve operations I touched on before. Here’s how the OPRF actually works:

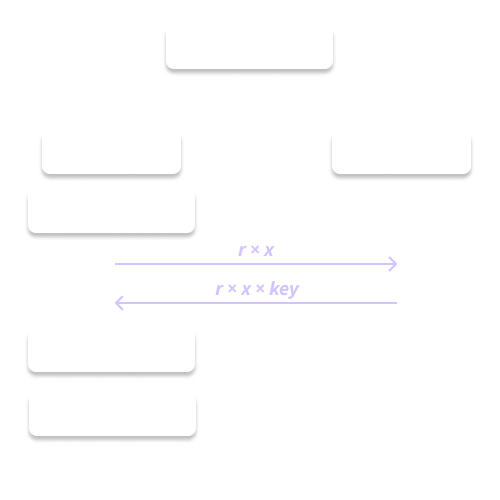

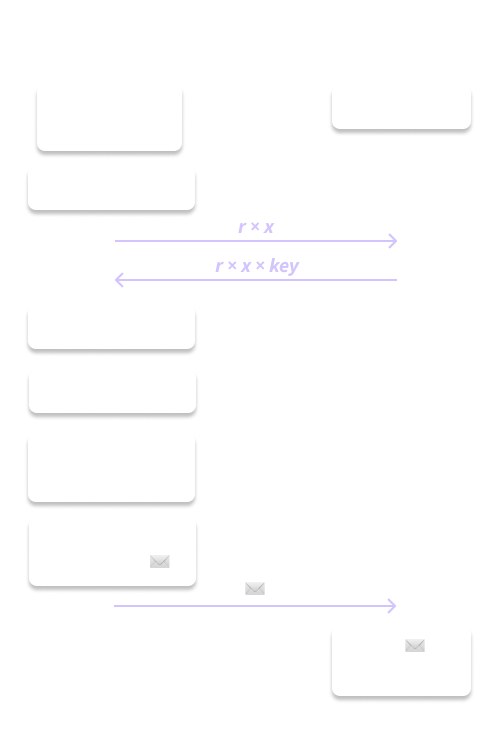

Figure 4. The full OPRF exchange.

- The client has

x, which is a number it wants to keep secret. It multiplies this point by the curve’s basepoint, so now we have a point. Let’s call this point x_point. - To keep it secret, the client generates a random number

r, which is called the blinding factor. The client calculatesr * x_pointand sends that to the server asclient_input. The server doesn’t knowr, so it can’t get the originalx_pointback. This protects the server from learning what the client inputted, but it’s easy for the client to undo this later. - The server receives

client_input, and multiplies it by its own secret number,server_input. (In the diagram, I called this secret numberkeyto save space.) This makes the output= client_input * server_input = r * x_point * server_input. The server can’t learn the actual execution output without the blinding factorx_point * server_inputnor thex_pointitself, because that peskyris there. - The client receives

output, and multiplies it by1/r. This lets it recoverserver_input * x_point— remember that division by a number is easy. However, the client still can’t learnserver_inputeither — remember that division by a point (x_point) is hard.

To summarize:

- We want to end up with the client’s input multiplied by the server’s input, without either party knowing the other’s value.

- The property that dividing by points is hard prevents the server from learning the client’s blinding factor or secret point and similarly prevents the client from learning the server’s secret.

- The property that dividing by numbers is easy enables the client to unblind the result to get the required

client_input * server_input.

Registration

That’s actually all the hard crypto out of the way! Let’s now cover the three main phases of OPAQUE: the registration, login, and key exchange. The first phase is registration, where the user will use their password (a string) in an OPRF exchange to get an encryption key that only they know that they then can use to encrypt their keypair data.

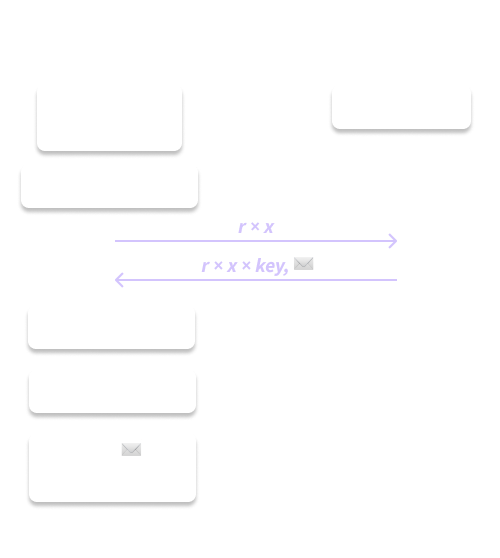

The registration revolves around an OPRF exchange.

Figure 5. OPAQUE registration.

- The client transforms their password into a point on the curve. This is done via ‘hash-to-curve’ functions that allow you to take arbitrary inputs to points on the curve. This is the

x_pointin the OPRF explanation above. The client then blinds their password point with some random blinding factor,r. - The server receives this

client_input. The server generates a user-specific keypair that’ll just be used for this user. This user-specific private key will be theserver_inputin the OPRF explanation above. It multiplies theclient_inputwith itsserver_inputand returns this value to the client, along with the server’s public key. - The client receives this

outputand unblinds it. The client now hasx_point * server_input. Let’s call this unblinded outputrwd— it’ll be used as the key to (symmetrically) encrypt what we call the envelope. - The client generates an envelope, which includes a new keypair that the client will use in communications with this server. It also puts the server’s public key into this envelope. The client then encrypts all of this with the

rwdand sends the encrypted envelope to the server. - The server saves the encrypted envelope so the user can access it again later. It can’t decrypt this envelope, since it has no way of unblinding its output to recover the

rwd.

Note that in every step of this process, the server will never learn the password nor the rwd used to encrypt the envelope, so the client can safely trust the server to store its information. This is critical for end-to-end encryption systems.

A fun challenge: given the protocol as specified above, can you find the DOS attack vector?

It's possible for a malicious user masquerading as the client to intercept the server's output and unblind it with some random number, making the `rwd` that the malicious user calculates meaningless. This doesn't matter, though, because it can then encrypt jibberish with the `rwd` or just directly send junk to the server, which will happily store it under the original user's identifier. When the original user tries to log in, they won't be able to decrypt the envelope they retrieve from the server, which effectively DOSes their account for any future use. This means there needs to be some way of checking that the original user is the same one who provides the blinded input and the encrypted envelope.

My supervisor pointed this out in my initial implementation of OPAQUE, and I was pretty confused when I saw that none of the other implementations on GitHub handled this in any way. I ended up asking Brooke Zelenka about it, and she pointed me to this section of the OPAQUE spec, which states that registration requires some other method of the server authenticating the client to ensure that it's talking to the right one. I think you can get past this if you assume enough things about the communication channel on which messages are exchanged, but I just slapped some signatures onto the messages to ensure authenticity and called it a day.

Logging in

Logging in also relies on a similar OPRF exchange. This time, the user needs to recover rwd so it can decrypt the encrypted envelope that the server returns.

Figure 6. OPAQUE login.

- The client transforms their password into the same point on the curve, and chooses a new random blinding factor

r. The client blinds their password point and sends it over. - The server receives this

client_inputand multiplies it with the sameserver_inputsecret that it used during registration. The server sends thisoutputalong with the stored encrypted envelope to the client. - The client receives this

outputand their envelope. It unblinds theoutputto recover therwdand uses therwdto decrypt the envelope. The user has now recovered their service-specific keypair and can move onto a key exchange or further communications with the server, since the decrypted envelope will include the server’s public key.

The two main benefits of OPAQUE were that it prevents the client and server from learning anything about what the other party’d stored or used to compute the function and that it avoids offline brute-force attacks. We’ve previously discussed how the OPRF provides this first property via the blinding factors and elliptic-curve cryptography, but let’s also briefly touch on the brute-force attack part. Without the OPRF, you might just encrypt the envelope with your password directly and send that to the server to store. This is both less secure than using a key, which is likely longer and has more entropy, but also allows any malicious parties, including a dishonest server, to intercept your encrypted envelope and mount an offline brute-force attack. In theory, the cryptography should ensure this takes a very long time, but the OPRF gives you the additional guarantee that any attacker must interact with the server to get their password guess multiplied by the server_input. This means the server is able to detect and rate-limit password attempts, making brute-force much slower than it would be otherwise.

The KE-rry On Top

The final piece of OPAQUE is the key exchange that needs to follow in order to derive a shared secret with which to encrypt all following communication. I focused less on this part of the protocol, since for my project we were only interested in the recovery of the client’s keypair from the envelope. As well, once you’re done with the OPRF exchanges, you’re in some sense ‘back in safe territory’ — there are plenty of key exchange protocols proposed, and you could probably plausibly choose any one of them. HMQV, a Diffie-Hellman variant, was chosen in the original OPAQUE paper for its performance. However, Cloudflare’s OPAQUE explainer leverages TLS as an AKE, and the specification mentions another variant using a SIGMA-I Diffie-Hellman variant.

For the sake of completeness, I’ll briefly cover the HMQV calculation used in the original OPAQUE paper. We want to derive a shared secret that both the client and server can calculate, and use this as a key going forward.

- As part of the login (or in a separate round-trip message), the client chooses a random number

c. It multiplies the curve’s basepoint with this to get a public pointC. This is sent to the server. - Likewise, the server chooses a random number

sand multiplies it with the curve’s basepoint to getS. - Both client and server then compute a couple of hashes (remember that these are effectively numbers, not points.) First, the client computes

blinded_session_identity = H(client_identity, server_identity, r)with its blinding factor. Then, lete_u = H(C, server_identity, blinded_session_identity)ande_s = H(s, server_identity, blinded_session_identity). The exact details of this are less important to the overall protocol — this just ensures you’re talking to the right person. - Then, the client computes its shared secret as

H((S + e_s * server_public_key) * (c + e_c * client_private_key))and the server computesH((C + e_c * client_public_key) * (s + e_s * server_private_key)). The first parenthesis of each expression contains the public parameters that are known from the other party, and evaluates to a point; the second parenthesis contains the private parameters from the party computing the hash and evaluates to a number.

If we expand both sides, we’ll see that what’s being hashed is the same. Feel free to skip the proof if you’re happy to just trust that the above are equal, but it’s neat looking at variants of Diffie-Hellman to prove how both client and server derive the same secret. I’d encourage you to give it a go — it’s very satisfying to see everything fall into place and the base math isn’t challenging, though keeping all the variables in line and recognizing when to factor terms in and out can be a nice puzzle. Let G be the curve basepoint:

(S + e_s * server_public_key) * (c + e_c * client_private_key) // what the client hashes

= (s * G + e_s * server_public_key) * (c + e_c * client_private_key)

= (s * G) * (c + e_c * client_private_key) + (e_s * server_public_key) * (c + e_c * client_private_key) // distribute the multiplication

= (s * G * c) + (s * G * e_c * client_private_key) + (e_s * server_public_key) * (c + e_c * client_private_key)

= (s * G * c) + (s * G * e_c * client_private_key) + (e_s * server_private_key * G) * (c + e_c * client_private_key)

= (s * G * c) + (s * G * e_c * client_private_key) + (e_s * server_private_key * G * c) + (e_s * server_private_key * G * e_c * client_private_key)

= (s * G * c) + (e_s * server_private_key * G * c) + (s * G * e_c * client_private_key) + (e_s * server_private_key * G * e_c * client_private_key) // rearranged terms

= (s * G + e_s * server_private_key * G) * c + (s * G + e_s * server_private_key * G) * e_c * client_private_key // factor out c and e_c * client_private_key

= (s + e_s * server_private_key) * c * G + (s + e_s * server_private_key) * e_c * client_private_key * G // factor out G

= (s + e_s * server_private_key) * (c * G + e_c * client_private_key * G) // factor out first term

= (s + e_s * server_private_key) * (C + e_c * client_public_key)

= (C + e_c * client_public_key) * (s + e_s * server_private_key) // what the server hashes

This completes the authenticated key exchange, and in turn, the OPAQUE protocol!

Conclusion

When I was first looking into implementing OPAQUE, my supervisor sent me the original paper as some helpful reading, but after seeing the PDF was 61 pages long, I bailed out to go read through the Cloudflare explainer instead. The original paper only has the full protocol laid out on page 47! The rest of the paper, and even the protocol description itself, is very dense — I suppose it’s nicely concise for those who have been in the field for long enough that they can parse the math at first glance, but trudging through all of that isn’t fun for a first-timer. I found the crypto explainers in general to also be at weird levels of abstraction that didn’t immediately make it clear how primitives built together, particularly for topics like elliptic-curve cryptography or OPRFs.

In general, I’ve noticed that theoretical crypto papers always start with a sea of security games where they prove the correctness and security of their protocol, but not actually explain the protocol until later, as if the protocol is an afterthought that derives naturally from the security games. Again, this probably makes sense for the cryptographers who are focusing on the security, but you’d think you’d put your major contribution up front in the paper. Another thing I’ve noted about crypto papers is how little discussion they usually have. Unless it’s an applied crypto paper where the system has been fully implemented and benchmarked, there’s usually at most a page or so of discussion, which mostly consists of re-explaining that they protocol is better than the others that currently exist. The conclusion is also usually on the order of a paragraph or two, which is a far cry from the systems/HCI papers that I’d read. As well, one thing that’s nice is that the modern crypto papers in major journals are mostly all available freely via the IACR. Having almost all my references centralized on the IACR archives and the IACR having a sequential numbering scheme have had the side effect of me memorizing the numbers of the key papers I’ve been referencing over and over again, to the point that I can type in the first digit out of the three or four digit ID and have Chrome autofill the rest as the first search result. Such is crypto research.

I came into this project not really having much crypto background besides understanding the basics of public key cryptography and what an elliptic curve was. The main resources I used to hack my way through were Wikipedia entries, which were usually less notation-heavy than papers, Cloudflare explainers published via their blog, and, in an unusual-for-me turn, ChatGPT. It’s surprisingly decent at explaining crypto and math topics — I was very wary of it getting things wrong, but it turns out even if it’s messing up some of the details, it’s good enough at imparting the intuition that lets you get a skeleton of an implementation done, enough to check it against the expected outputs from Wikipedia or the actual paper. I did write the code myself, since it wasn’t quite understanding the libraries I needed to use, but it did a fair job of pointing me in the right direction or mentioning keywords (even if they were explained in the wrong contexts) that I could check against other resources. I’m decidedly less anxious about using ChatGPT as an assistant now, and I expect it to keep giving me enough nudges to make my way to the end of my project.

Anyways, I hope this explainer has been clearer than the usual seas of math notation that never tell you how things fit together or how the intuition works. I’m thinking of doing the same sort of explainer for some other cryptography topics that I’ve had to wrestle with for my project recently, like Shamir secret sharing. As my supervisor said, warning people not to roll their own crypto is a bit patronizing when you think of it: it discourages folks from really understanding the protocols they’re relying on and creates this out-group of folks who think they’re not good enough to do crypto. It emphasizes this mindset where people aren’t trusted to understand any crypto well enough to not mess it up. While this was probably trying to prevent people from writing their own very easily breakable ciphers and things of that more trivial nature, I think it’s a bit of a gatekeep-y refrain. Go forth and implement your own OPAQUE — hopefully this explainer has made you a little less oblivious to OPRFs and OPAQUE and how to build them!

-

Admittedly, not generally known for being truly secure, particularly against malicious Telegram employees, but it marketed itself as something different to the conventional chat platforms I’d used before then. ↩︎

-

When I say ‘hard’ in this post, I generally mean ‘currently no one thinks it’s possible’, but that doesn’t roll off the tongue quite so well. If it makes you happier, replace ‘hard’ with ‘requires exponential-time brute-force’, and ’easy’ with ‘polynomial-time or less’. ↩︎