The Oulipian Oeuvre.

Published 28 December 2025 at Yours, Kewbish. 3,532 words. Subscribe via RSS.

Amidst the Great Lock-in of September-December 2025, we realized, well, we would need something to lock in for. Thus, the personal curriculums trend was born. It’s 2025, and learning is cool again! Disconnect. Be book-smart. Swap doomscrolling for dopamine menus and self-curated syllabi. Pop “anti-brainrot” activities like antibiotic amoxicillin for a infected, festering mind.

I jest. I also ended up drawing up a reading list and getting super into something niche. That something was the Oulipo, or the Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, a French-based group of mathematicians, pataphysicians, and writers, among other métiers. To grossly approximate, they invent constraints, often somewhat logical or geometrical in nature, and then produce everything from poems to novellas and plays in this elaborate game of “bet you can’t”. Perhaps the easiest to explain is Georges Perec’s La Disparition (A Void), in which the constraint is “no e’s” and of which the result is a 200-some page murder mystery where every e-like reference turns into a fatal plot device.

The Oulipo’s a bit hard to describe, even for members. One recurring description is that an Oulipian is a “rat in the labyrinth of their own construction”1. Of course, said rats deeply enjoy their labyrinth-construction and continually outdo themselves.

I think the Oulipo’s neat. The computer scientist in me is drawn to the constraints, the inner child who grew up constantly reading to the prose and prosody. This post summarizes some of the related readings I’ve done this last term. I hope it serves as inspiration for your own personal curriculums, or perhaps prompts you to build one of your own.

Start Here

The Oulipo has a very vast oeuvre, but of the books I’ve read I’d start with these three.

To get a taste of what types of forms and wordplay, All That Is Evident Is Suspect provides an accessible overview, with an extract from every member. It’s edited by two Oulipians themselves, Ian Monk and Daniel Levin Becker, both of whom have extensively translated other Oulipians into English. I think it’s worth reading even after having engaged with the most popular “classics”, since the editors have explicitly chosen lesser-known or unpublished extracts from the “big names” and gone a bit more in-depth for those lesser-known. Access to Oulipo work is rare enough, since it’s primarily published in smaller fasciscules, and access to work in English is even rarer. I really enjoyed the cross-cutting in the anthology. I would also be remiss not to mention the book design: my library edition didn’t come with the book jacket, but the binding and book stamp are very aesthetic. The typography and design is reminiscent of Stripe Press, if more graphically bold. This genuinely may be the most beautiful book I’ve seen.

To go more in-depth, I’d go with Life A User’s Manual by Georges Perec. This book is what got me into this Oulipo mess in the first place. In a roundabout way, it tells the story of a wealthy eccentric and the lives of those he’s drawn in around him in a certain tenement block. It’s perhaps intimidating for its size, but a joy to read. I found it a great example of Perec’s storytelling’s cohesion and of his style: there’s some listicle-like parts that are very Perec. These parts are quite prolix, so I skimmed over them as a compromise. As a story, it certainly stands alone, but there’s also a behemoth of constraints behind it that really make Perec’s effort impressive. These rules are published in the Cahier des charges, which I honestly found less compelling than expected. It was almost a letdown to see the coulisses and the poor typography didn’t make it inviting. I’d skip the Cahier and just read the Wikipedia or academic papers for the constraints if those interest you.

For a non-fiction take on the Oulipo as a group, Levin Becker’s Many Subtle Channels was a lovely glimpse into the movement’s history. Levin Becker was first a grad student studying the Oulipo, then was later co-opted into it, which gives Levin Becker, and by extension this book, a unique perspective: transitioning from an outsider to an insider. Many Subtle Channels present some ideas for what the Oulipo is, what it was, and what it isn’t anymore. Levin Becker chronicles many individual members’ contributions, humanizing their quirks and mannerisms. He also touches on the “in-joke” and puzzle-driven atmosphere I’ve noticed, where folks keep trying to find connections and constraints where maybe they aren’t any. For example, in All That Is Evident Is Suspect, there’s these large block letters at the start of each extract, and I figure there’s a hidden message I haven’t yet found. I really liked the behind-the-scenes look at the extracurriculars of the group, from the readings, to the camps, to the idiosyncratic rules, and the dinners. Besides this, the writing style is very approachable and I vastly preferred it to the other Oulipo non-fiction I’ve read. It also inspired me to start noting down more vocabulary — Levin Becker’s writing has this fun mix of prosaic and provocative.

Diving In

Admittedly my coverage of specific works was limited by what was easily available at my library, but here are some other books I had the chance to read.

Winter Journeys is an elaborate game of “yes, and”, sort of a Book of Genesis of the Oulipo’s tradition of anticipatory plagiarism. It’s “collaborative fiction”, comprising a collection of short stories by various members. Perec kicks it off with an essay about a marvellous, unassuming book of poetry from which the great masters have all plagiarized. Naturally, such a discovery has wide implications for the integrity of European literature, so many Oulipians proceed to do their own research and add their own findings to the tale. Somehow it also meanders into how the Oulipo came to be, and the in-universe “truth” around Perec’s story. It gets pretty meta. There’s so many references and bits and pieces that it’s a whirlwind to follow: I made a website to explore each story graphically. See also: Stephen Frug’s review.

Unrelated: somewhere in this book, perhaps the epigraph of the second story, there’s this beautiful quote that’s sparked much reflection:

What if these yesterdays consumed our fine tomorrows?

La Disparition, or, in English, A Void, is often the first work presented to an Oulipian novice, because the constraint, at face value, is the easiest to explain. (I did the same in this post’s introduction.) It’s Perec’s postmodern mystery set in a world without the letter “e”. It becomes a fun game to figure out why certain plot events happened: it’s very “all that is evident is suspect”. The plot is very fitting and indeed incorporates this lack of “e”, so prominently so that when a reviewer lambasted the book as a failure, everyone instead laughed at him for entirely missing the point. I read this after reading a separate non-fiction review of Perec’s work, Constraining Chance (discussed later), so I had the context of Perec’s war-torn childhood and his family’s deportations. Mother (« mère »), father (« père »), and family (« famille ») all can’t be spelled without an “e”, hence they cannot feature in the book. In French, “they” (« eux ») sounds like the phonetic pronunciation of “e”, so when “e” has disappeared the pun is that “they” have disappeared. These darker elements don’t surface in the book, but I thought it was helpful to understand.

Spoilers: some notes I found

- Anton is insomniac because you can't spell "sleep" (nor « sommeil ») without the letter "e".

- The barman dies because there aren't any eggs (« oeufs », which sounds like "e").

- Raymond Q. Knowall must surely know all about Raymond Queneau.

- Douglas perished after singing "mi", which in solfège represents "e".

- The wrist markings and the tanka outline's shape bring to mind the sinuous curves of an "e" and the less sinuous lines of an "E", respectively.

A Void ended quite abruptly, but by then the jig of the constraint was quite obviously up. What’s to do with the leftover “e"s? Perec’s answer was to write about an orgy (as one does2). In particular, an orgy at a see involving a jewel heist. Les Revenentes (The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex) was published three years after its antithesis. The story descends into increasingly incomprehensible madness as it goes on: the initial mise-en-scène is still more or less grammatically intact, but some of the later misspellings were head-scratching (apparently ‘shet’ means ‘shut’, and I still haven’t deciphered ‘cwm’). The subject matter is quite explicit, and I think I would have got the gist without the gristle had I just read the first few pages. If anything, it’s a fair source of vocabulary: I wouldn’t have learned the word “ephebe” if not for their role in the fête. The translation was the most impressive feat of the work — I have no clue how Ian Monk (or, E. N. Menk) managed it.

I read The Exeter Text as part of the collection Three. Perec had suggested Les Revenentes be published alongside two other “ludic” novellas, a request that was only honoured posthumously and, as of date, only in English. It neatly cuts across his canon, including Which Moped with Chrome-plated Handlebars at the Back of the Yard?, The Exeter Text, and Perec’s last work, A Gallery Portrait. The collection includes a short foreword before each story. In the case of Which Moped, a story of a soldier hoping to escape deployment into the Algerian War, this helps underline the political undertones, from Perec’s involvement with the then-new literary review La Ligne générale, which was supposed to revitalize a novel view of communism. There’s a certain resignedness and darkness even given the levity of writing, which liberally repeats structures for emphasis but with small variations each time. The index of literary devices is very Oulipian and makes the “inside jokes” quite upfront and accessible. On the other hand, A Gallery Portrait turns instead to a painting of other paintings and an art collection that isn’t what it seems. Its structure and subject matter also feels very Oulipian, if less explicitly so. The listicle sections, focus on painting, and art provenance themes are all reminiscent of Life A User’s Manual, and the final twist of the story was paced like that of A Void. I really liked the temporal and technique variety in this collection, and it’s a nice foray into some of Perec’s shorter works.

So far my reading has been very Perec-heavy, but I also read Zazie Dans le Métro (Zazie in the Metro) by Raymond Queneau. It’s about a little girl who terrorizes Paris as an agent of chaos, at first in search of the Paris metro. It’s very comic, like Which Moped. It was written before the Oulipo was founded but I find it captures much of the same tongue-in-cheek energy. It’s much more comprehensible than The Exeter Text but does make use of “neo-french”3, much swearing, and odd language registers. This made it difficult to translate, but Queneau entrusted Barbara Wright, a piano accompagnist-turned-translator with the task. I think the link between rhythm and style is quite interesting and certainly translated well. I also watched the 1960 film adaptation, which is extremely slapstick and funny. I thought the sound effects and pacing were good, and the visual effects are crazy given how long ago it was filmed. I had intended to watch the film as French practice, but the older accent was a bit too difficult to follow. For the full comedic experience I think both reading the book and watching the film is worth it.

Other Works

I haven’t read these in full, but they’re fairly popular. Otherwise, I’ve heard of them in passing and they’re on my TBR.

There’s plenty of Oulipian poetry constraints, like Jacques Jouet’s metro poems or the variable-length sonnets. Several Oulipians also have poetry collections, including Perec’s La Clôture. This collection in particular contains franglais poems, an extremely long palindrome, and some other fun heterogrammic constraints. My French isn’t to the point I could “get” the flow without a dictionary and the constraint descriptions: again this brings to mind Levin Becker’s question in Many Subtle Channels of whether a work is worth reading if we know the constraints ahead of time. Perhaps worth a flip through, even just to marvel at the palindrome.

L’Organiste Athée (The Atheist Organist) is a book without a book, consisting only of prefaces and postfaces to a missing main text. It was written by Latis, who would christen the Oulipo as we know it and illustrate its first logo. I couldn’t find this published standalone in an Americas-accessible format, but there’s an extract in All That is Evident is Suspect.

Oulipians like writing about vignettes of everyday life, often variations on the same subject matter. Sometimes these exercices are more adult. Harry Mathews wrote Singular Pleasures, which I will let you guess as to the subject matter of. It was followed by Hervé Le Tellier’s La Chapelle Sextine (The Sextine Chapel). Indeed, The Sextine Chapel’s dedication reads “for Harry Mathews, these plural pleasures”. This latter has a very interesting constraint arrangement: if you’d prefer to skip the contents, the back of the book has a neat diagram. I think the diagram alone already suffices for intellectual titillation.

Other times the vignettes and exercises are really more banal. in Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien (An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris) Perec spent a few days at the same square in Paris and described much of what he saw, punctuated by repetitive bus patterns. This seems like the sort of undertaking I’d do.

In All that is Evident is Suspect, Levin Becker leaves some recommendations for other Oulipian anthologies, including Warren Motte’s Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature, Alastair Brotchie’s Oulipo Compendium, The Noulipian Analects edited by Christine Wertheim and Matias Viegener, and the Verbivoracious Festschrift Volume Six.

As for more meta non-fiction, I read Alison James’ Constraining Chance: Georges Perec and the Oulipo right after Life A User’s Manual and before any other Oulipian works. It was the first time I learned of this “rats in their own labyrinth” framing of the Oulipo. The monograph was admittedly a struggle to read given the myriad literary references and my inexperience with dense literature studies. However, it connects many of the themes in Perec’s work to his earliest political writing and family history, and presents the symbolism in relation to other literature. In retrospect it was good context, but I’m not sure if I would have the patience to sit through this again.

If you’re more of a documentary person, there’s apparently a documentary of Oulipians going around Paris to describe their favourite spots. It’s called L’Oulipo court les rues (de Paris). While the trailer is here, that seems to be the only digital version available, since it was distributed as a DVD. However, there’s a more recent version sponsored by the region of Aix-Marseille-Provence available on Vimeo, featuring fewer members.

Fantastic Books and Where to Find Them

As I mentioned above, for us Anglophones on this side of the Atlantic ocean it’s a bit hard to come across Oulipian content. The group’s oeuvre remains mostly in French with limited publishing: the typical Bibliothèque Oulipo fasciscules are printed in runs of 250. Even the larger collections, like Atlas Press’ edition of Winter Journeys, tend to go out of print quickly. Oulipo work also doesn’t tend to be published digitally in ePub or PDF format, which also rules out most forms of digital piracy. One of the reasons my list focuses so heavily on Perec is because of the prevalence of translations and the slightly larger publishing runs, which means it’s feasible to find them in libraries.

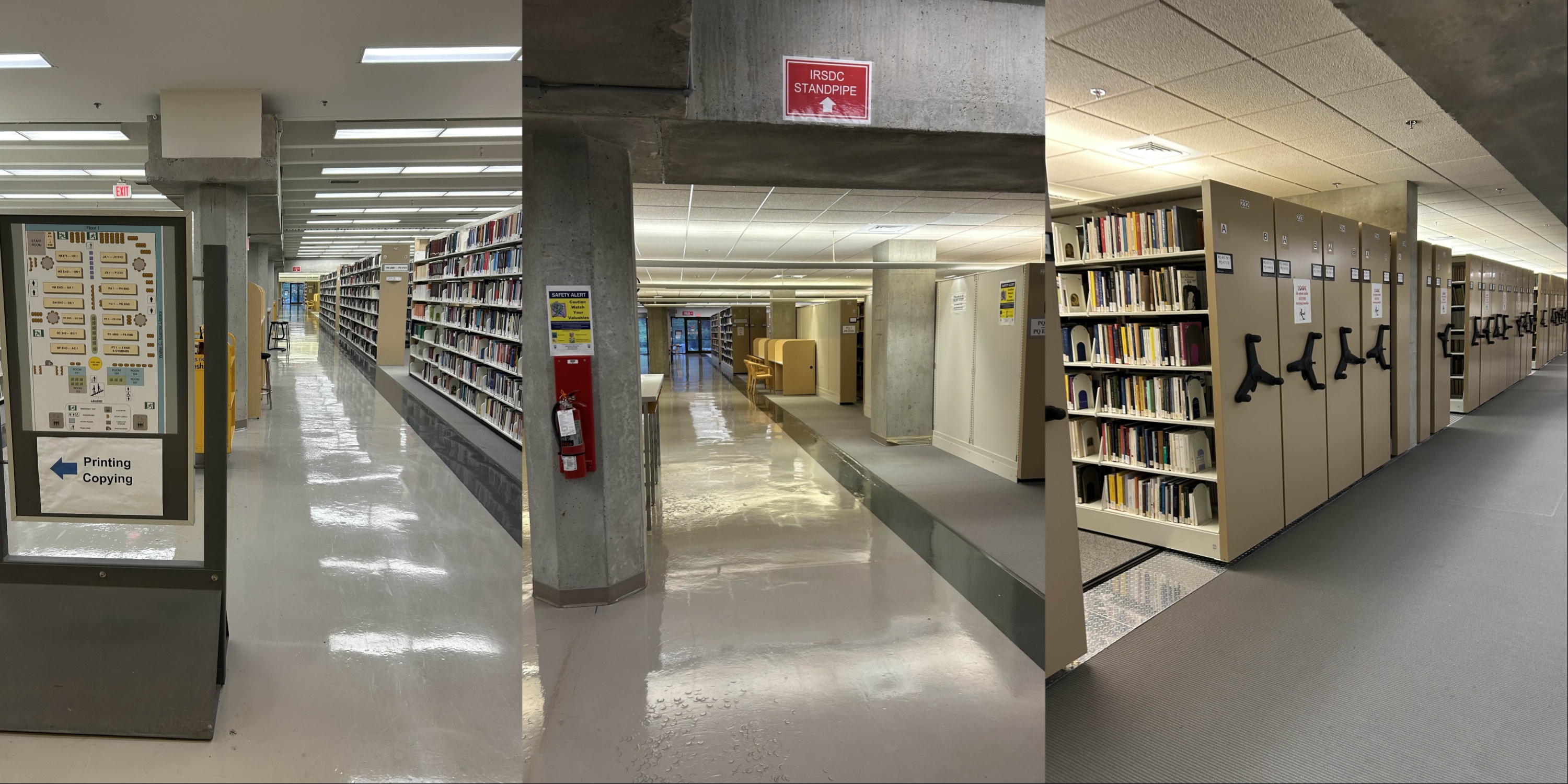

I’ve found the UBC library quite impressive in its coverage: they have a copy of most of the Oulipian books I’ve tried to find. I made a lot of trips down to the Koerner stacks this term, and at this point I can easily find my way to the general Oulipo section (for the non-fiction or the anthologies) or to Perec and Queneau’s shelves (conveniently on adjacent stacks so I don’t have to crank as far). Go down to the bottom floor of Koerner, walk straight forward til the ceiling beam with the red sign, turn right, and you’re there. The general section is on the first or second stack from the left; Perec and Queneau’s shelves are a few more cranks to the right, closer to the big pillar. I’d recommend going sometime without anything in particular in mind and seeing what you can find.

Figure 1. Navigating the Koerner Stacks.

The Oulipo and larger fanbase also have a decent web presence online.

- The Oulipo themselves have a website with a lovely index of constraints. They also have an Instagram which is quite active4.

- The Oulipotes (“friends of the Oulipo”) maintain an email list which I haven’t personally joined but is apparently quite lively and is the go-to forum for Oulipo amateurs. It features in Levin Becker’s contribution to Winter Journeys.

- Zazie Mode d’Emploi is an association inspired by the Oulipo that seems very active and runs workshops and festivals in the Lille region.

- If you poke around there are also plenty of offshoot collectives and folks doing Oulipo-inspired writing challenges. The Found Poetry Review had an Ouliposting-themed National Poetry Month a while back. UBC’s Emerging Media Lab won a Large TLEF grant to build a VR Procedural Poetry Funhouse with inspiration from Oulipo.

It’s often a bit of an archives game to find more obscure Oulipian texts or history, but the above would be my starting points.

Conclusion

If the Oulipo is hard to pin down, what’s a bit easier to articulate is the experience of reading the Oulipo. It feels like being in on a joke, tongue firmly in cheek. My best friends and I often latch in on a bit when we’re bantering, and in levels of increasing irony and sarcasm we add to this exercise of “yes, and”: to me Oulipian writing feels like these exchanges. The work is clever, without pretension. And there’s a full spectrum of ways to engage, from tracking down every nod to the theme or constraint to just reading for the plot and the story: both levels are equally enjoyable. Topics and settings seem vaguely banal and everyday, and the premises are never quite so far-fetched that they don’t click.

Levin Becker described being an Oulipo reader well in Many Subtle Channels — he concludes it by comparing Oulipian works and potential literature to “language in the hands of [the] crafty reader”. “To live your life craftily […] is to move through it […] knowing you hold the tools to give it shape and meaning.” Becoming part of this in-joke and in-group means joining into this big “yes, and”, and I think there’s plenty of fruitful whimsy in that.

I should caveat this reading list with the fact that I’ve engaged with most work via their English translations. I thought it’d be better to more easily appreciate the constraints and storytelling, instead of struggling with vocabulary. If anything, noticing little differences and idiosyncrasies due to the translation made me appreciate the translators’ role more. For example, the awkward verb tenses in a piece in Winter Journeys reflect what I assume is the use of the conditional in French. Likewise with the neo-French or odd turns of phrases across the other works. Gilbert Adair, Ian Monk, Daniel Levin Becker, and Barbara Wright, among others, have done an incredible job.

I suppose a personal curriculum wouldn’t be complete without some assignments, so here’re some ideas:

- Go to your nearest library and find its Oulipo corner, or where some of your favourite Oulipian authors are shelved.

- Write an Oulipo-inspired piece with one of the listed constraints. Extra credit if it’s in French (as a French learner this is much harder than it seems.) Extra extra credit if you do this with no prior knowledge of French and sheer dictionary-delving will.

- Choose a constraint, come up with its moral antithesis, and write a text about the original constraint while respecting its opposite.

- Write your own sonnet, following Queneau’s rhyme scheme, to add to the A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems. This website might be helpful, and includes English translations. Congrats, this gets you to almost four hundred thousand billion poems.

I’m wrapping up my own Oulipian syllabus for now, but I hope this has been a helpful starting point for anyone interested in the idea of constraints and potential literature. Happy reading, happy holidays, and happy labyrinth-building!

-

Beyond the literary references, I think there’s plenty of value in this expression as applied to most of our lives. Perhaps the Oulipians were the anticipatory plagiarists of “you can just do things”? ↩︎

-

This is more common than expected in Oulipo works. See the Other Works section on The Sextine Chapel and Singular Pleasures. ↩︎

-

Imagine the equivalent of Zazie saying “six-seven”, but in a time period closer to ‘67. ↩︎

-

For a group that sells fasciscules exclusively via email to a

free.fraddress (the French spiritual equivalent tohotmail.com), I was impressed. ↩︎