Everything I Know About Stacked PRs.

Published 11 June 2023 at Yours, Kewbish. 2,082 words. Subscribe via RSS.

Introduction

I spent last summer interning at Repl.it, the browser-based coding platform that makes it easy to build and collaborate. I interned on their Workspace team, and primarily worked on porting their GitHub import flow to Nix (and another super-secret project that hasn’t been shipped yet). It was an incredible learning experience – I was mentored by insanely smart people and granted the autonomy to own development of an improved product flow. Check their platform out if you haven’t already: it’s just as amazing as the team behind it!

It’s ironic that while working on GitHub imports to support Replit users’ dev workflows, a major technical challenge would be wrangling GitHub to support my dev workflow. While Replit’s engineering team has no prescribed pull request submission process, I quickly learned that the most efficient way to get PRs reviewed quickly was to make them small. But when you’re working on adding a new feature or flow, the amount of code changes needed is generally big. How do you split up a huge PR into smaller ones while making sure that they’ll get merged in order and that they make sense as smaller units?

The solution was stacked pull requests. Instead of making a larger PR, split the PRs up into logical working chunks and stack them on top of each other. Let’s say you’re working on adding a new modal dialog for some flow. Inside, there’s some interaction that calls out to a new API that you also implement, and some interaction that uses an existing API in a new way. Instead of submitting this all as one big PR, you can create a base PR with just the UI changes (git checkout -b add_modal_ui from main). Then, you can create another PR on a new branch off of the base PR with an implementation of the new API and hooking it up to the UI (git checkout -b add_new_api from add_modal_ui). After that, you can branch off this second PR again to integrate the existing API (git checkout -b add_existing_api from add_new_api).

The PR stack ends up looking like this:

main

└── add_modal_ui

└── add_new_api

└── add_existing_api

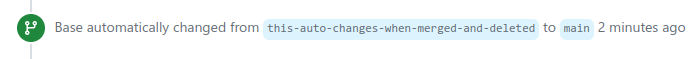

GitHub has a good UI for submitting stacked PRs that you might not have ever noticed. When submitting a new PR on a branch, you can choose the base branch that you submit your PR to. For example, when submitting the PR on the add_new_api branch, choose add_modal_ui. If you daisy-chain these, GitHub will automatically update the base branch of each PR in the stack as they get merged.

Figure 1. GitHub automatically changing a PR’s base branch.

Because each individual PR builds on the previous one, but is a logically coherent and small addition, each PR can be reviewed individually. This speeds up PR review since reviewers don’t have to comb through a hundred changed files trying to make sense of what affects what. It’s easier to articulate intention with smaller PRs too, leading to better communication.

A PR stack typically gets merged from the leaf back down to the root PR (in the example, from add_existing_api to add_modal_ui) and back to the main development branch1. This means that all your changes can still end up on the main branch as a single unit, as in the “good ol’ Big PR” approach, but they’ve likely been easier to review and work on.

Sometimes the PRs can even be as small as a single commit, and the PR stack is essentially a PR of smaller PRs. Think of stacked PRs like an extension of the commit history feature within the GitHub code review pane. When reviewing big PRs, you can look through commit history to see how things were put together. Stacked PRs operate on the same principle: they isolate changes to their smallest logical units, but just do so more explicitly than with multiple commits.

Stacked PRs also kept me unblocked during the summer, even when I had lots of changes on the go that depended on each other. I didn’t have to wait for a feature submitted as a large PR to be reviewed before working on something that built on top of it. This is especially nice when I submitted the base PRs for review before starting to work on PRs that build on it, since this way you can keep the stack small but keep the momentum of feature development going.

Stacked PR workflows aren’t perfect. I spent a lot of time painstakingly resolving branch conflicts this summer23, especially after PRs lower in the stack had significant changes requested. When you’re working on many different features within a feature, your PR stack can also turn into a gnarly PR tree. With more complicated changes to base PRs and inter-PR stack dependencies, we ran into what was lovingly known as ‘rebase hell’. As well, because PRs get merged into their parent PRs, the root PR still lands a big diff on the main branch, so take care to review changes in staging carefully before merging down. With stacked PRs, you also can’t test individual PRs in production (unlike in short-lived branch workflows) which might be a deal-breaker if your local environment is limited.

In spite of all this, I still think stacked PRs are a useful tool in managing large PRs efficiently. This post covers everything I’ve learned about working with stacked PRs, so you can skip the rebase hell and take advantage of some hard-learned workflows.

Merging Upstream Changes

Let’s say you’ve branched off main like so:

main

└── branch1

└── branch2

You’ve made some changes in branch1 that you also want to incorporate into your changes in branch2: for example, branch1 was reviewed and someone requested changes on underlying code that was developed in branch1 but also depended on in branch2. Or perhaps main has had some significant updates that change your development environment, and you want to get those into your branch2 as well.

The typical solution for this is while in branch2, run git merge branch1 to get the new commits of branch1 into branch2. Alternatively4, you can git rebase branch1 on branch2, resolve merge conflicts, then git push -f onto branch2.

Another strategy is to run git rebase --onto=main branch1 branch2 on any branch, then git push -f. If branch1 has already been merged, you might need to find the merge-base, or the ‘common ancestor’ between main and branch2 with git merge-base branch1 branch2 and run git rebase --onto=main [merge-base-result] branch2.

Avoiding Squashed Upstream Changes in Bottom of Stack

In this footnote1, I said to avoid merging from the bottom of the stack up since this usually leaves a bunch of duplicate commits in the branches on the top of the stack as the commit hashes change on merge. But let’s say you’ve gone ahead and done this anyway, resulting in:

main (with branch1 changes)

└── branch2 (now with duplicate commits)

This gets tricky. My strategy was to try to keep a list of commits from branch1 somewhere pre-merge, so that these commit messages can be compared then against branch2. Run git rebase -i HEAD~x, where x is the point at which you branched off branch1 to branch2. Then in the interactive menu, drop all branch1 commits. After running git rebase main and resolving merge conflicts, branch2 should now only contain the changes unique to branch2. Run git push -f and you should be good to go! Phew.

Cherry-picking

Another alternative fix for the above situation relies on careful cherry-picking. Let’s say you’ve branched off of main like the previous example but have merged down branch1:

main (with branch1 changes)

└── branch2

And you’re in the same scenario: you need to get rid of duplicate commits in the new base PRs of the stack. Sometimes, when there are a few commits, it’s easier to build a new branch with cherry-picked changes from the old branch2.

Run git checkout main and git checkout -b branch2-new to create a new branch incorporating the branch1 changes with their new commit hashes. Then as with the previous section, note commit hashes of changes on branch2 and cherry-pick them over with git cherry-pick [commit_hash]. You’ll have to resolve conflicts along the way, but with smaller branches this can result in less resolution work than dropping commits and rebasing.

If all your branch2 commits are consecutive, you can cherry-pick a range of commits all in one go. Run git cherry-pick commit_hash_start^..commit_hash_end. The ^ denotes to include the first hash, and the .. denotes a continuous range between those two commits, inclusive.

Merging Changes From Downstream

Finally, let’s cover how to merge changes down properly. Let’s go back to the first example, and let’s say you’ve branched off main like so:

main

└── branch1

└── branch2 ✓

branch2 has been approved. (Maybe branch1 has as well, exciting!) The easiest way to merge things down to main from here is to go from the top of the stack (i.e. to go from branch2). This maintains commit hashes and avoids the complex rebasing strategies in the section above.

However, this results in larger diffs being applied all at once to main, so this may not be ideal for continually deploying environments where you’d like to test incrementally. This also might not be a great idea if main is significantly ahead of branch1 or branch2, which means there’s more opportunities for untested breakage due to new main updates. My strategy was to merge down into the second-to-last PR on the stack (branch1), and rebase main into that so I’d only have to resolve conflicts once. Then I’d test, and once I was sure things were working, I’d merge everything into main.

Conclusion

These strategies should be enough to cover most stacked PR workflows - the commands are relatively straightforward, and carried me through a successful internship. However, I’ve neglected to mention that there are tools out there that automate most of this workflow for you. While I haven’t used it, many of my coworkers at Replit were playing around with Graphite.dev at the time. It’s a CLI that builds on top of git to handle this lower-level rebasing for you, and automates creating stacked PRs complete with a stack summary message in each PR. It looked useful, especially for the automatic rebasing, but I didn’t want to bother migrating my workflow and learning new Git commands just then. I might check it out in the future though - if it can help me avoid rebase hell, I’m all for it.

There are also some Git plugins that don’t go quite to the extent of automating PR creation as Graphite does, but helps facilitate the details. I’ve seen git-stack and git-machete mentioned before, as well as ghstack as a lightweight Graphite alternative.

Despite all the intricacies of a stacked PR workflow, I’m still strongly convinced that these smaller PRs lead to more efficient PR review and faster development-feedback-ship loops. With it, I was able to ship features consistently and quickly last summer, and am still applying the same workflows at Cloudflare this summer. I’m sure this’ll also be the case in future projects and work. The tooling supporting stacked PR workflows is becoming more robust and mature, and I’m betting stacked PRs will become more and more prevalent in the coming years.

-

This leads to the caveat that the base few PRs must be approved before the leaf PRs can be merged in. It’s good to communicate that to your team when working with stacked PRs! Several times during my summer, my fellow intern and I made slow progress because we were constantly waiting for the base PRs to be approved and shipped before we could build on them again. Also try to avoid merging from the base up - this leads to a bunch of duplicated commits especially if your team uses the ‘squash and merge’ strategy. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

It got so bad that at one point my fellow intern and I Slack huddled for a couple hours just picking through rebase conflicts. We called it a rebase party (complete with :partyparrot:s). Near the end of my internship, ‘rebase hell’ became a running joke with my manager and some of my team. ↩︎

-

I recently learned about

git rerere, which can help with the repeated rebase conflicts that can arise with stacked PRs.git rererepersists conflict resolutions and automatically tries to re-apply them if the same conflict comes up again later on in the rebase process. ↩︎ -

My preferred strategy, because it didn’t leave merge commits in the history. ↩︎