The GitHub Graph.

Published 26 May 2024 at Yours, Kewbish. 3,915 words. Subscribe via RSS.

Introduction

In mid-April, I had the opportunity to speak at Open Source Summit North America 2024, held in Seattle. I spoke about research that I’ve been working with Professors Dongwook Yoon, Ivan Beschastnikh, and Cleidson de Souza on: characterizing open-source collaboration patterns from the GitHub Issues and PRs that they comprise. I was nervous attending my first real conference, let alone speaking, but it was an amazing first experience. Even though I was only there for a day1, it was an incredibly fulfilling one, and I’m grateful to the organizing committee for making the conference a welcoming, engaging success.

I’ll touch on more of my conference experience and some backstory (because oh boy, is there a backstory) in another post, but I wanted to first share my talk in post format. This article will be a transcript-style rehash of my talk based on my speaker notes, but if you’d prefer to watch my talk rather than read, I’ve also listed it here. The raw slides are available here.

Talk Intro

Hi friends! I’m Emilie, an undergrad at the University of British Columbia and software developer. I’ve recently had the privilege of working with Professors Cleidson de Souza, Dongwook Yoon, and Ivan Beschastnikh at UBC on the topic of understanding open-source development practices empirically, in the real world. We found that there’s a lot of hidden context and unspoken patterns that GitHub and other development platforms don’t highlight, and today, I’m going to show you how we revealed them. We analyzed over fifty large open-source projects hosted on GitHub and developed a novel graph-based perspective that we’re calling the PR-Issue Graph.

Today, I’ll cover our methodology, this PR-Issue graph’s attributes, and our workflow type definitions. You’ll walk away with a new outlook on managing open-source collaboration, able to recognize common workflow patterns and what they might mean for your community. I hope this talk will spark some discussion and brainstorming over how we can be mindful of these workflow types as we lead open source development efforts.

About GitHub

How many of you are familiar with GitHub? It’s a developer platform built on top of the version control software Git. You’ve probably already heard of it in some of the previous talks. GitHub is a popular choice among open source projects as a central platform for collaboration.

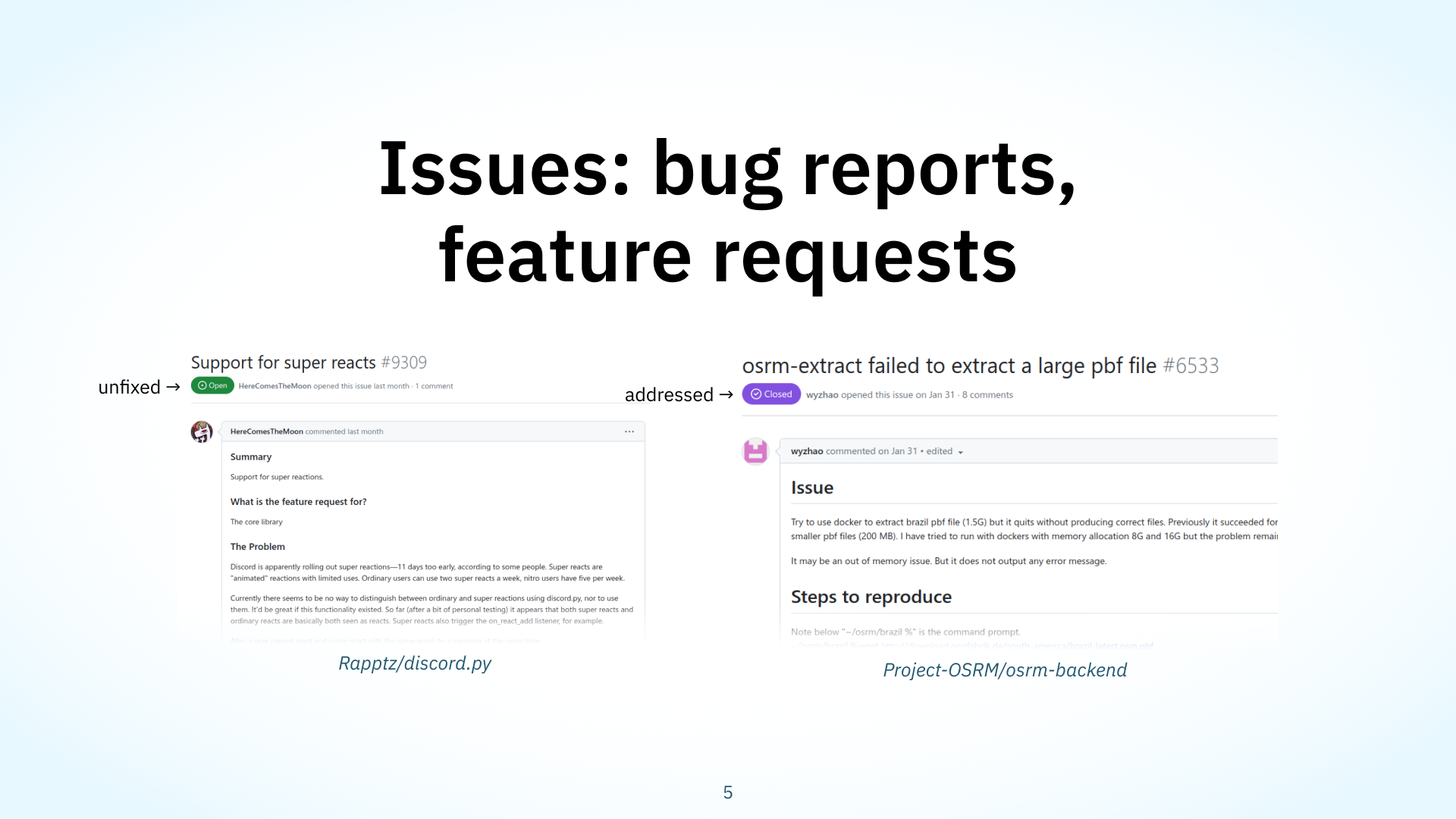

On GitHub, community bug reports, feature requests, or general discussion about projects are done on issues. On the slide are a couple examples of projects we’ve studied. I’d like to highlight that issues have a designated status. You can see that on the left, the issue is open, which usually means it hasn’t been addressed; and on the right, it’s closed, meaning someone has fixed the issue or the discussion has been deemed off-topic or closed.

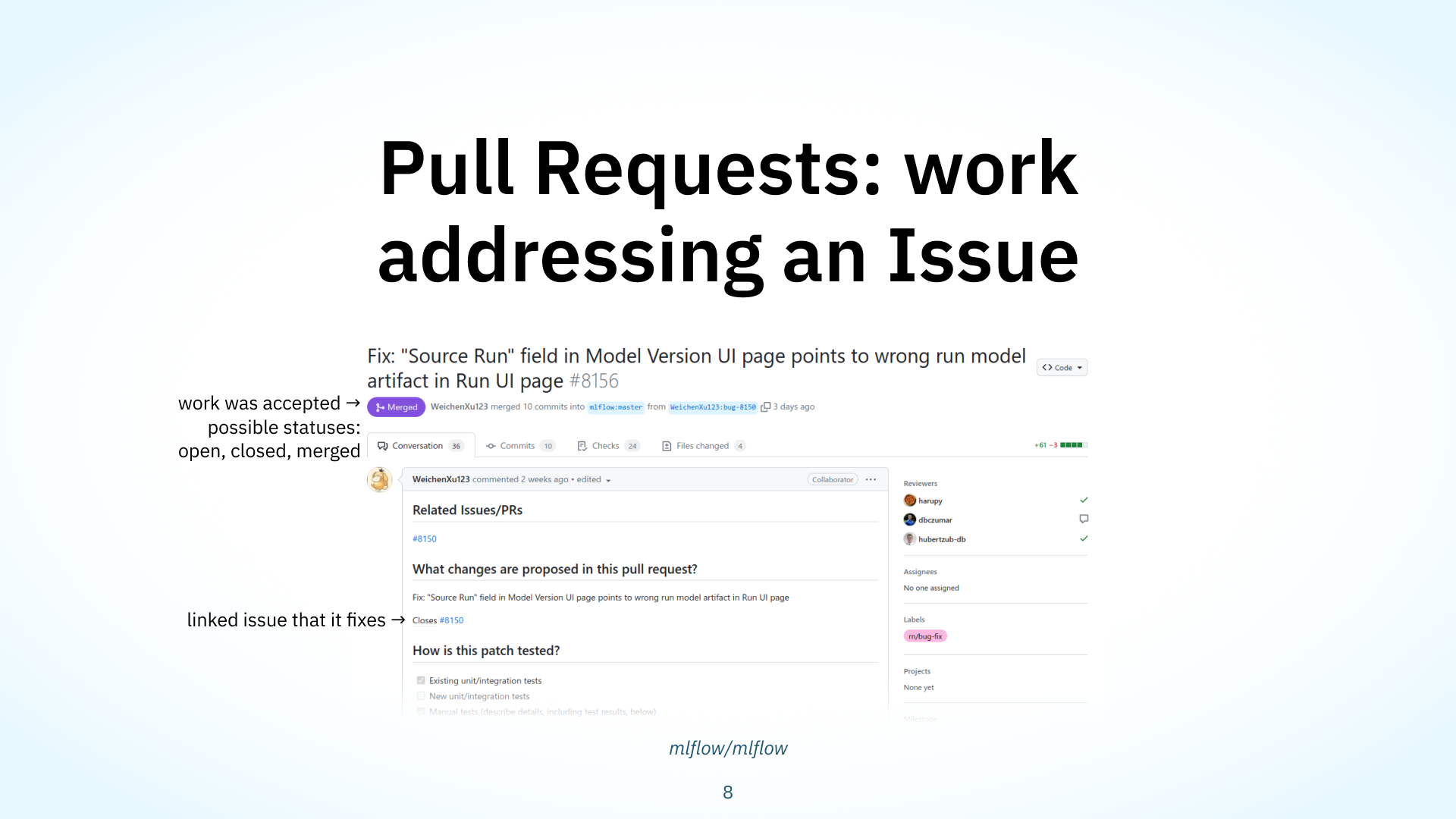

New code, perhaps addressing these Issues, is merged into projects via Pull Requests, or PRs. They also have statuses: open, if it’s undergoing or will undergo review; closed, if the work was unsatisfactory or extraneous; and merged, if it’s been accepted and integrated into the project. People discuss and review code in PRs. As well, folks can link to Issues in a PR: for example, if a PR fixes an issue that’s already been reported, contributors will typically link to the issue within their PR to create an explicit connection between the two.

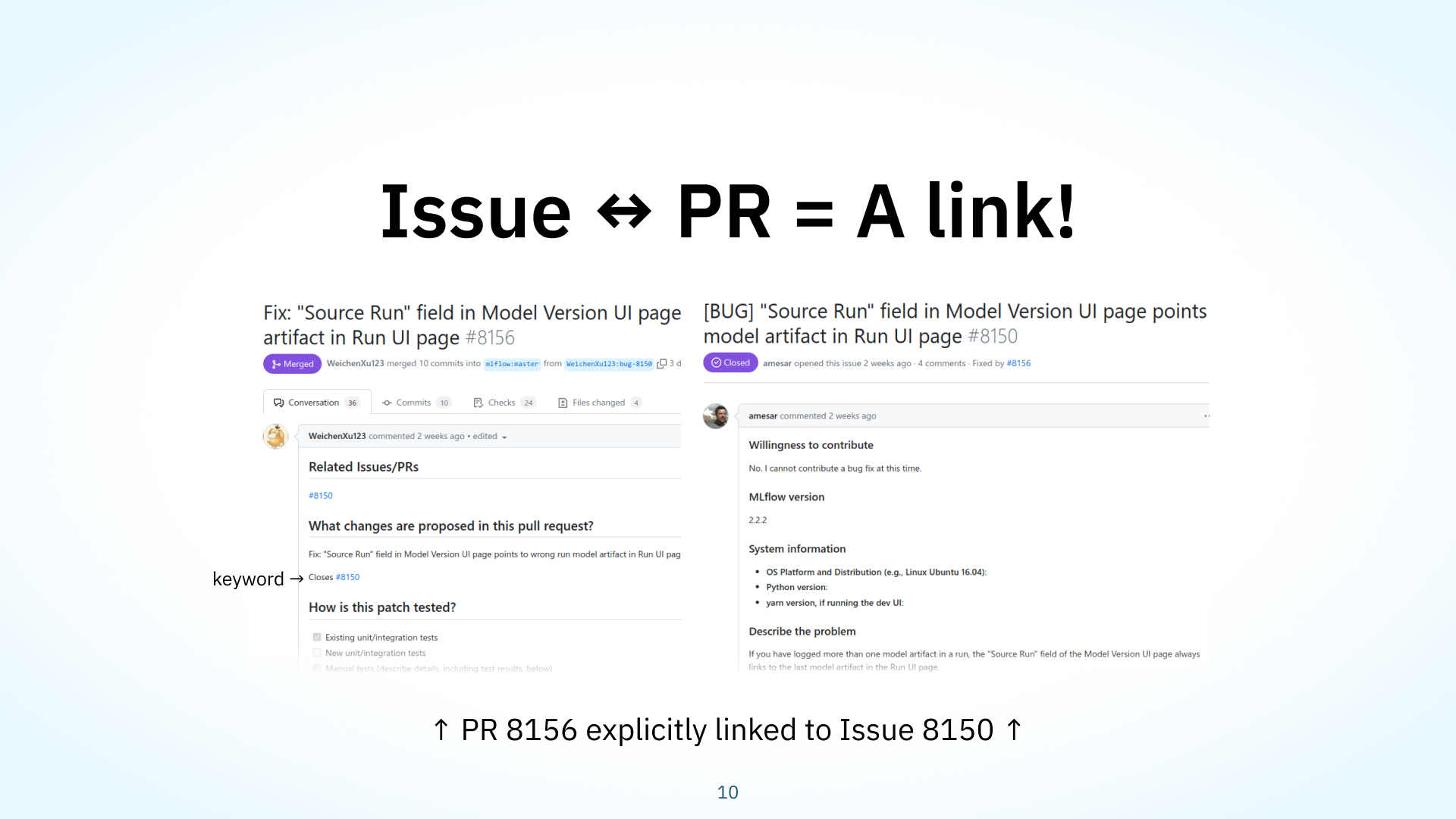

Here, that link has an explicit ‘fixes’ type. GitHub will automatically create two types of links for you: ‘fixes’ or ‘duplicate’. If you mention a keyword associated with ‘fixes’ or ‘duplicate’ with an issue number, GitHub will create a link with the appropriate type. Here, the link was created with the keyword ‘closes’, which is associated with the ‘fixes type’.

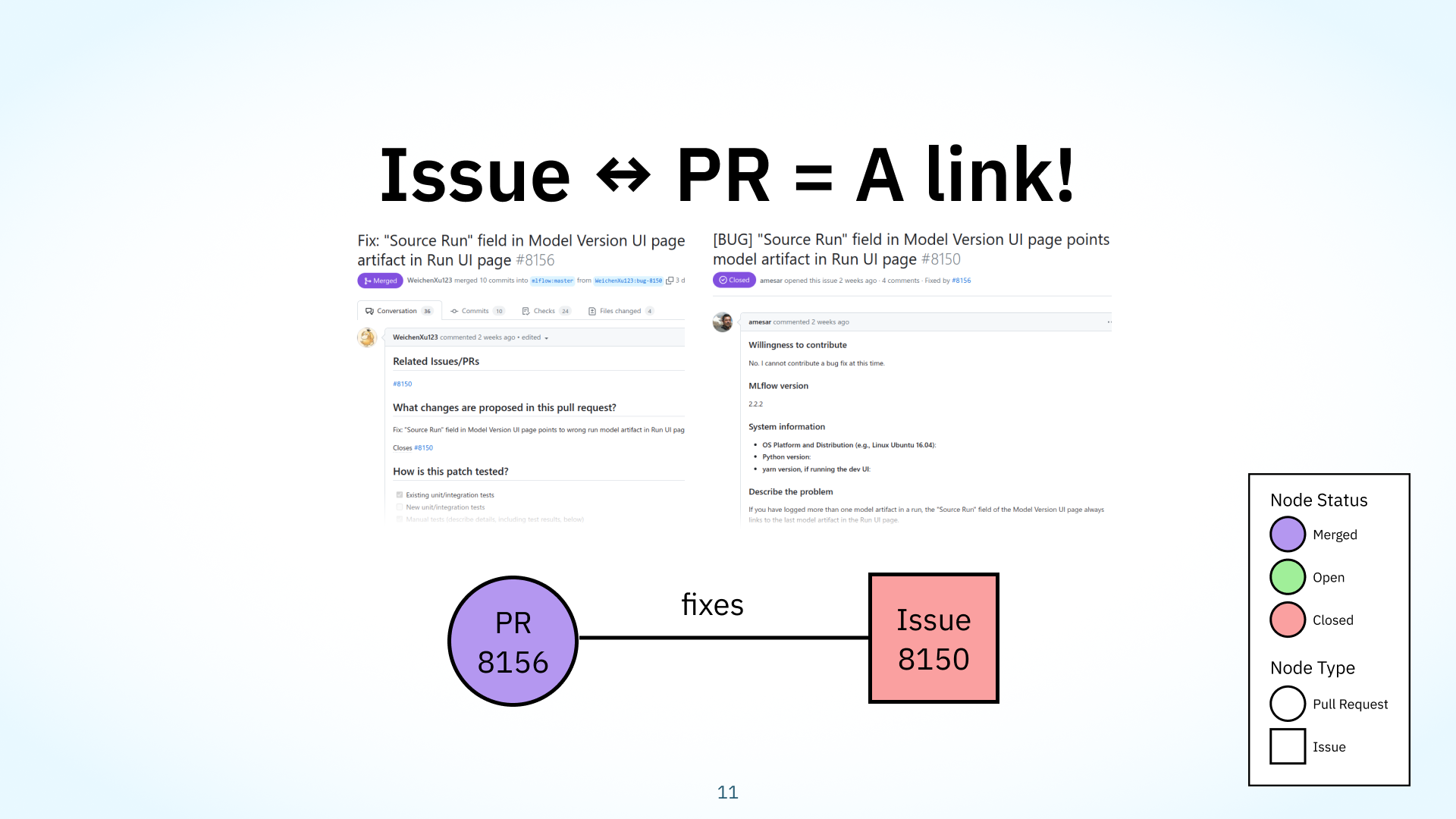

If we frame this as a collaboration graph for a second, we start to see something basic but interesting emerge. Let’s consider the PRs and issues as nodes, and the links between them as edges. We can model the different node types and statuses: so here, purple means merged, green means open, and red means closed, just like in the GitHub UI. This is a graph-based visualization of the example I’ve been showing: we have a problem (Issue 8150, the red square), and we have a solution (PR 8156, the purple circle), the PR fixes the Issue, and there’s nothing else connected to this work.

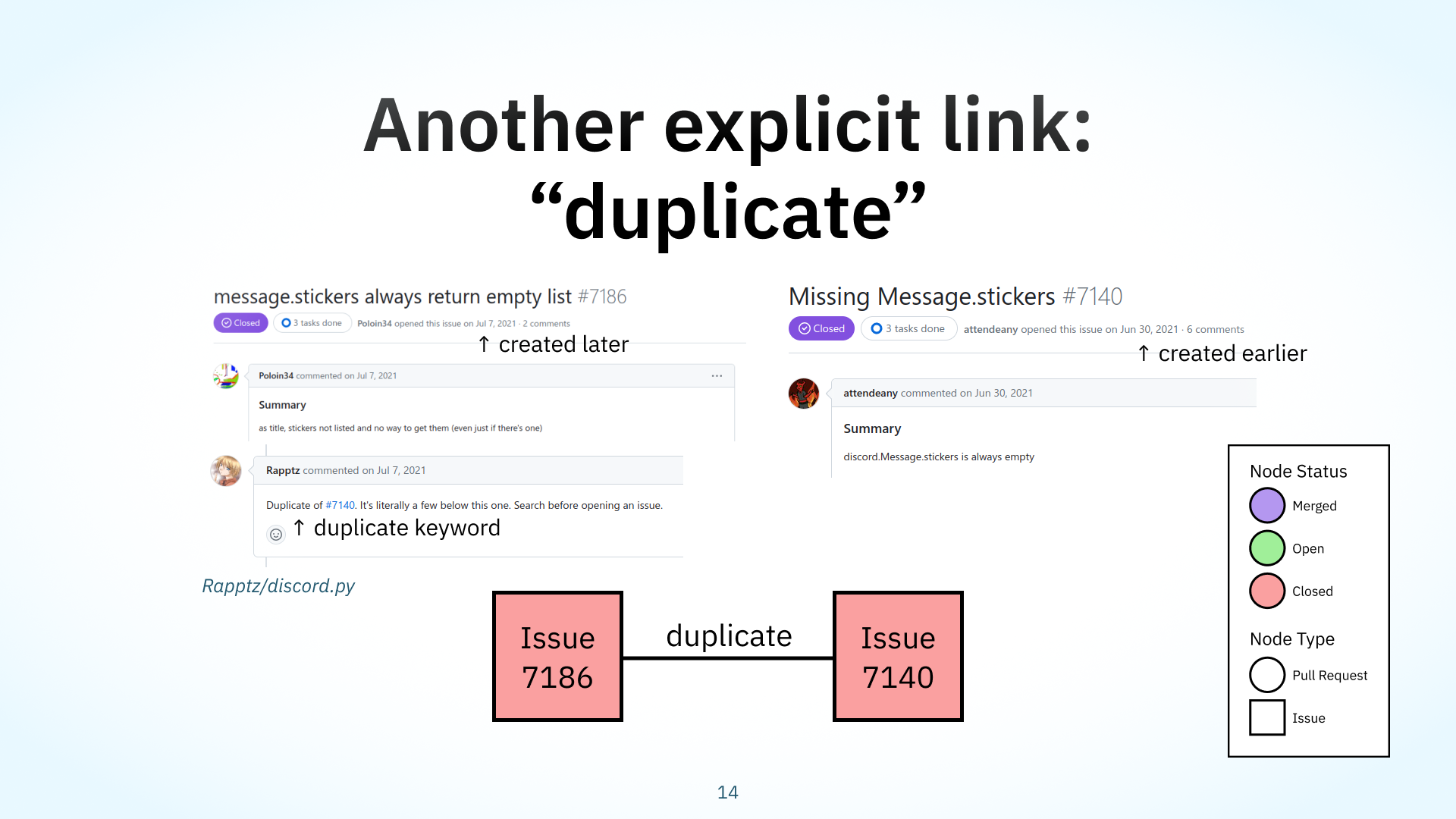

Here’s another example of this graph based perspective, this time with an explicit ‘duplicate’ link taken from a project called discord.py. Here’s a visualization of what that looks like. The problem reported in this issue on the left was marked as a duplicate of this other issue on the right. The issue on the right was created earlier and covers the same problem of a missing field.

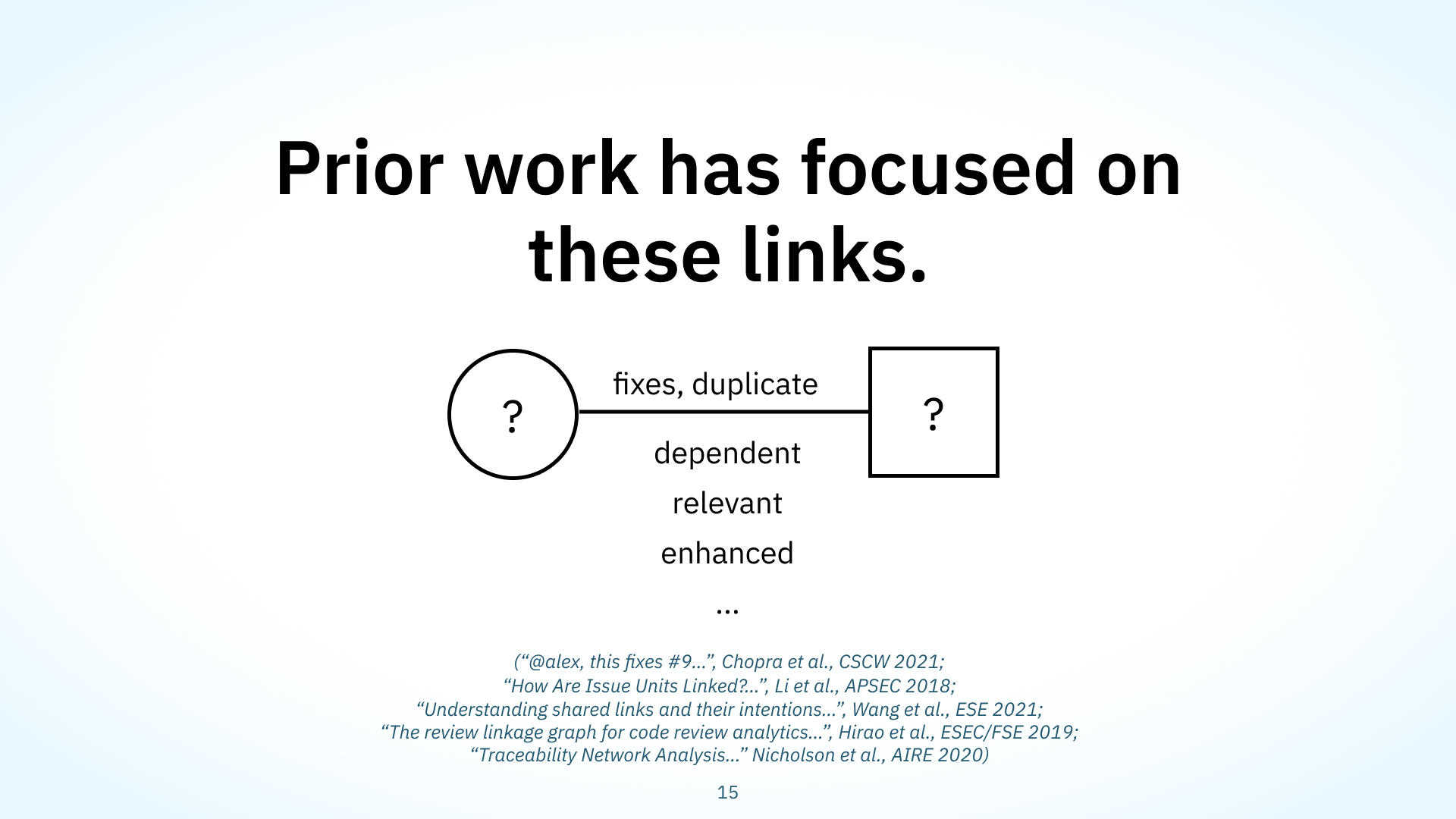

Prior work in software engineering research has focused on these links extensively. While the examples I’ve shown have explicit link types that are detectable and supported by GitHub, about 85% of links on GitHub don’t have a ‘fixes’ or ‘duplicate’ relationship, according to Chopra et al. Researchers have been primarily trying to classify these blank links into richer categories than just ‘fixes’ or ‘duplicates’, and many papers have built several distinct taxonomies for doing so, including link types like ‘dependent’, or ’enhanced’. Some work has also been done to do this automatically, with NLP classifiers.

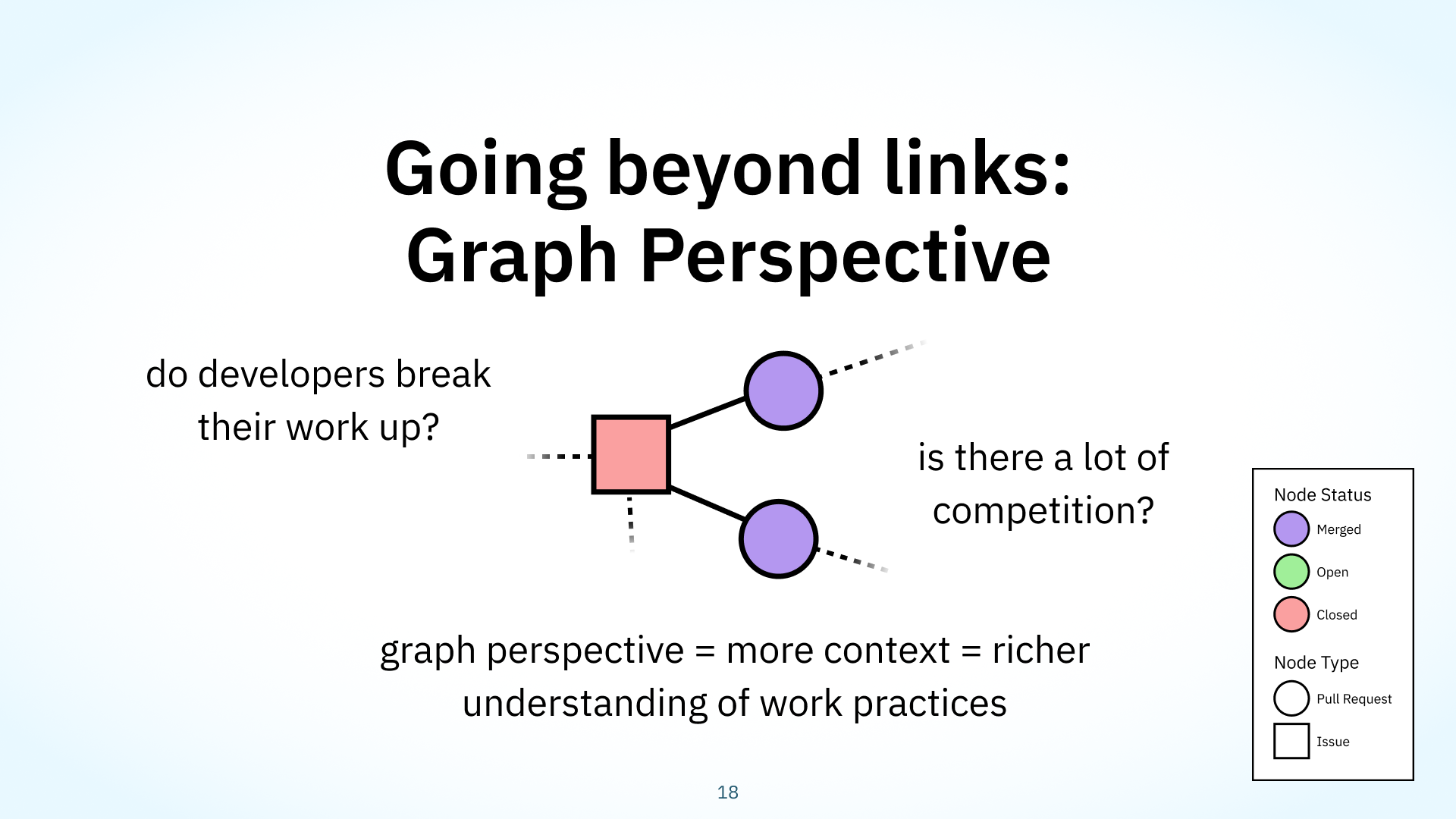

However, let’s take this idea one step further. We were interested in ‘zooming out’ of the prior, very focused research on individual links. Our research is the first to look at multi-node clusters of issues and PRs as a graph. This graph perspective grants us more context, as we simply have more metadata and relationships to examine, which in turn gives us a richer understanding of the work practices associated with each type of graph. For example, with more context, we can understand larger implications about the development work practices in a project, like if developers break their work down into small chunks for review, or if there’s a lot of competition in certain areas of the project. This graph perspective is what we’ve nicknamed GitHub’s PR-Issue Graph, and for the rest of this talk, I’ll show you what lurking insights about open-source collaboration we’ve found hidden in it.

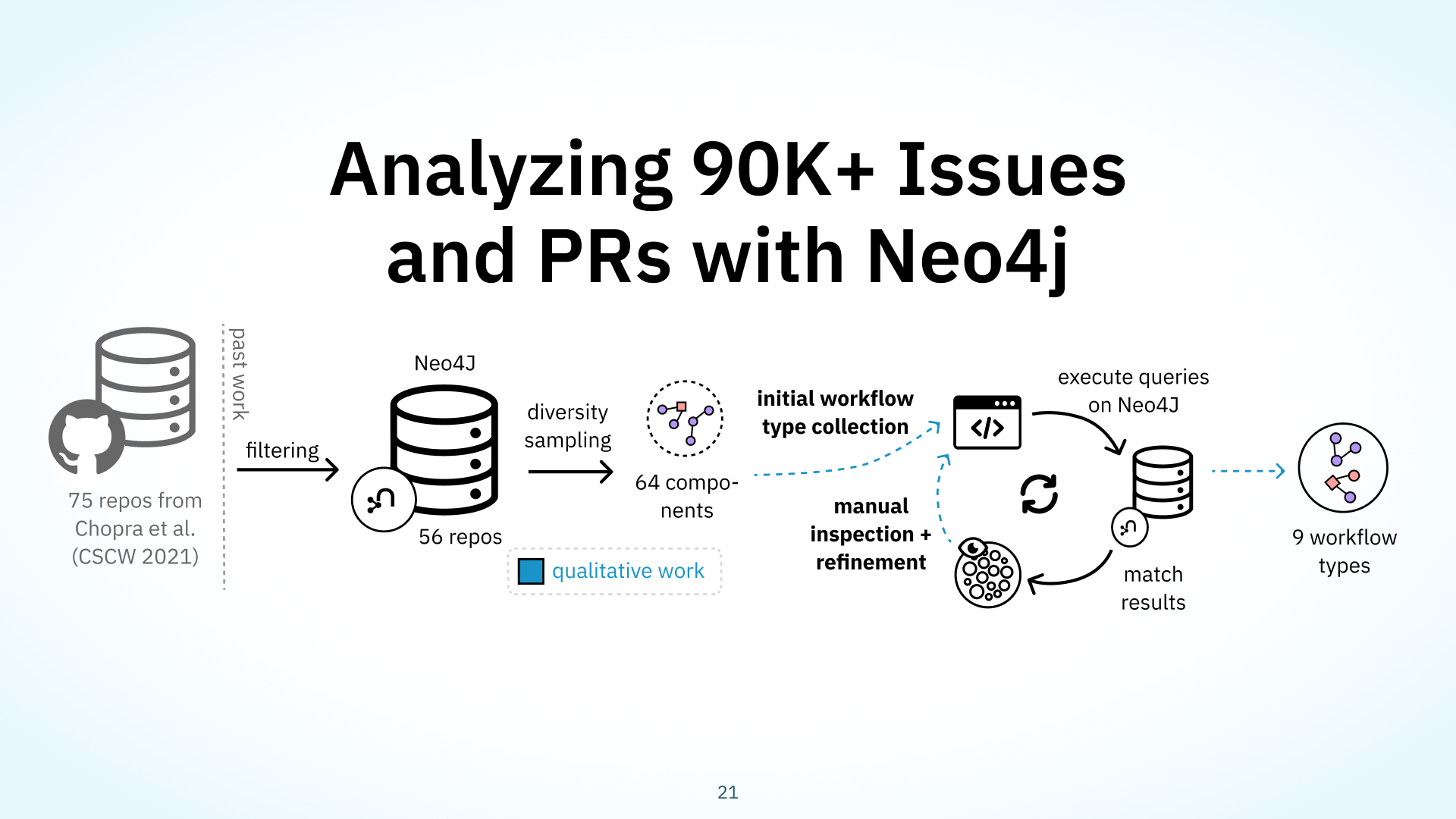

Methodology

You might be wondering how we did all this analysis. We chose to analyze GitHub as our platform of choice because of its popularity, its data availability, and the diversity of projects hosted on it. We initially scraped 56 popular projects on GitHub, based on a prior sample by Chopra et al. These cover a variety of topics, like machine learning with projects like mlflow and foundational technologies like gRPC. We downloaded the contents, metadata, and links of more than ninety thousand nodes. We used a diversity sampling technique to generate a sample of sixty clusters, or subgraphs, in which each link was manually coded into a list of extended link types. From there, we identified some repeated structural patterns that we thought could represent work practices in software development.

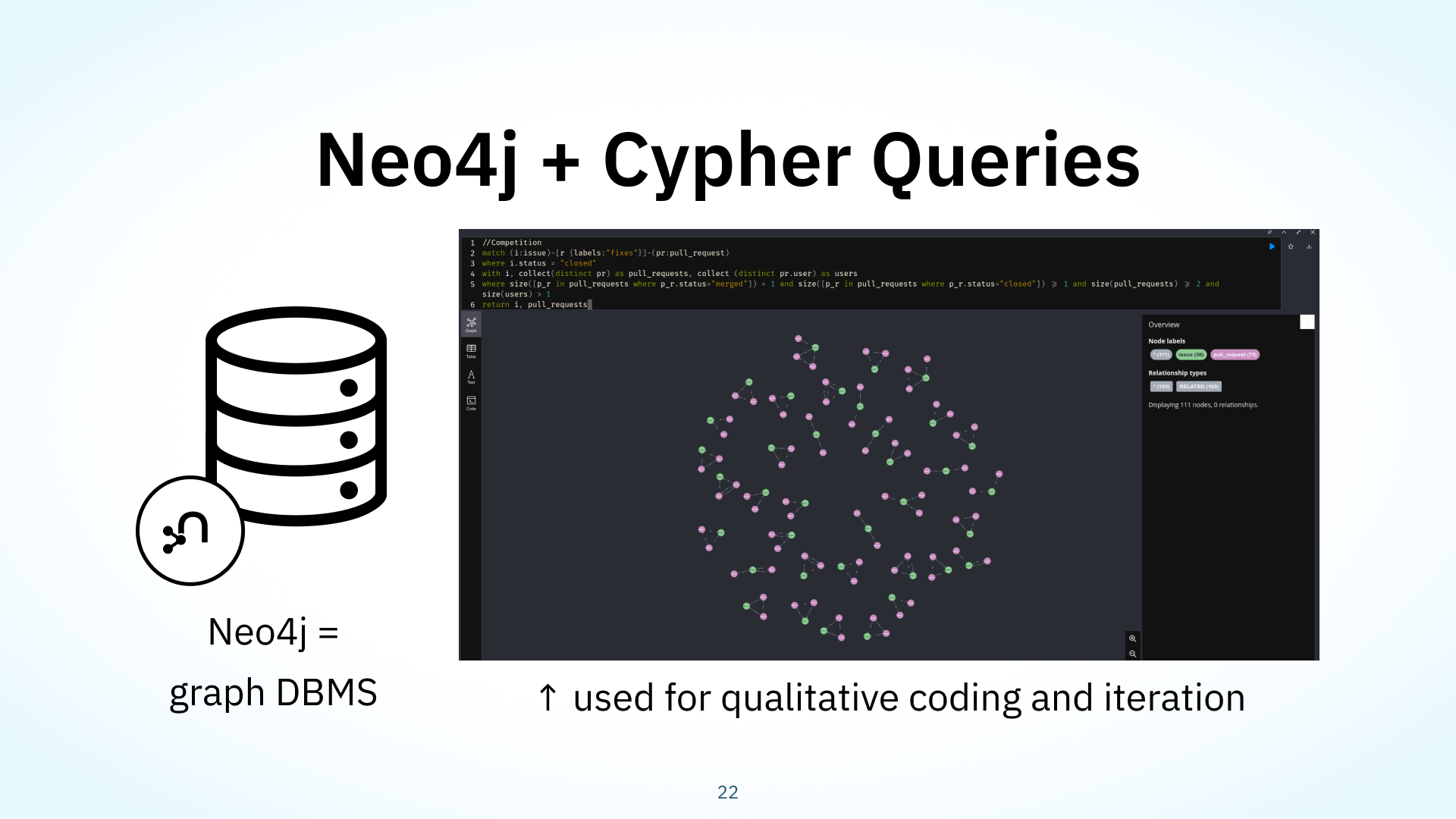

Next, we imported the issues and PRs and their metadata into Neo4j, a graph database software, and created reusable queries to search for all occurrences of these collaboration patterns. Onscreen, you can see an image of the built-in query browser visualizing some results.

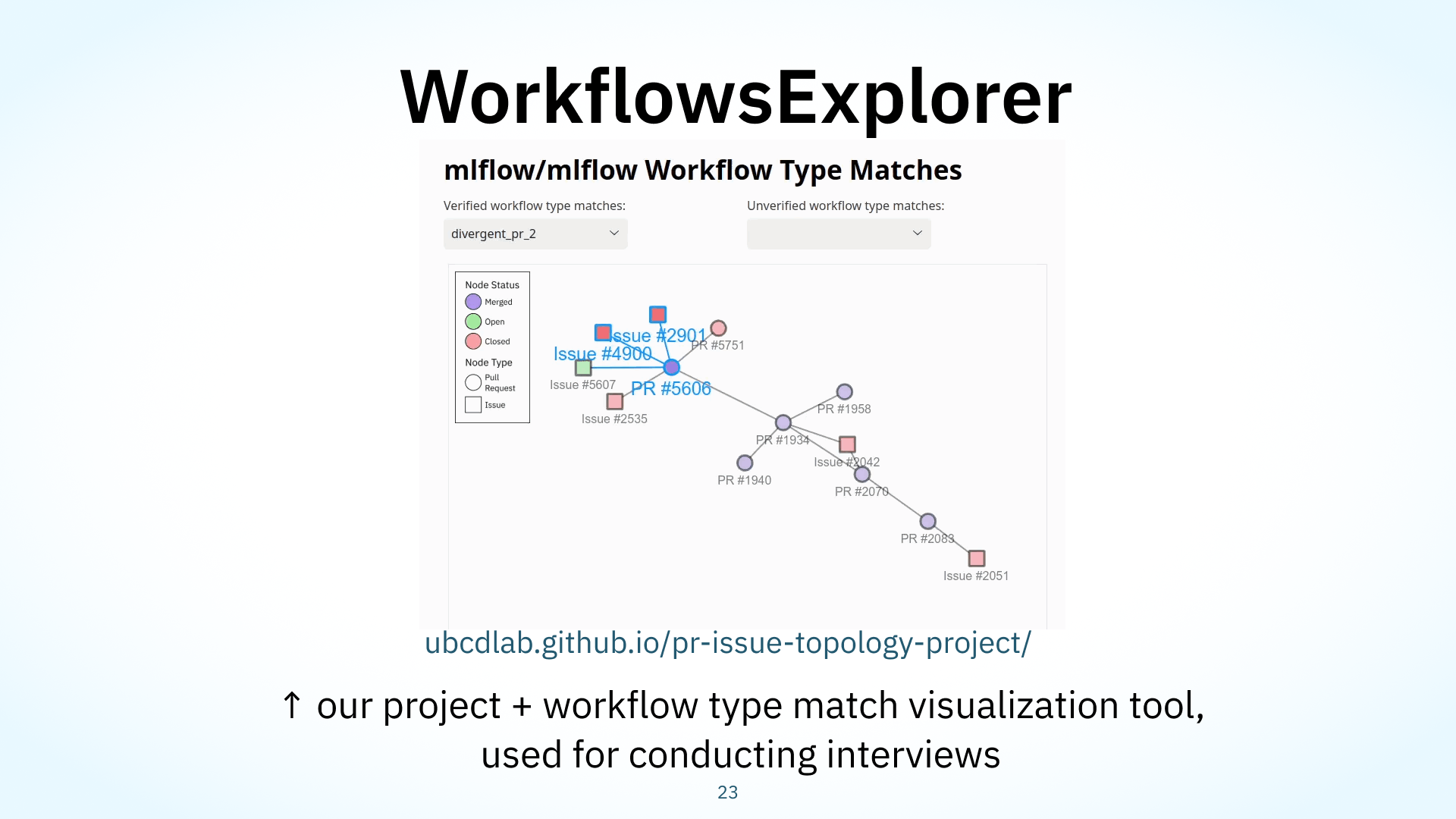

We also developed an image visualization module and interactive explorer tool that we used to streamline manual coding and validate our findings during interviews with open source developers. Here’s what this looked like.

Project Characterization

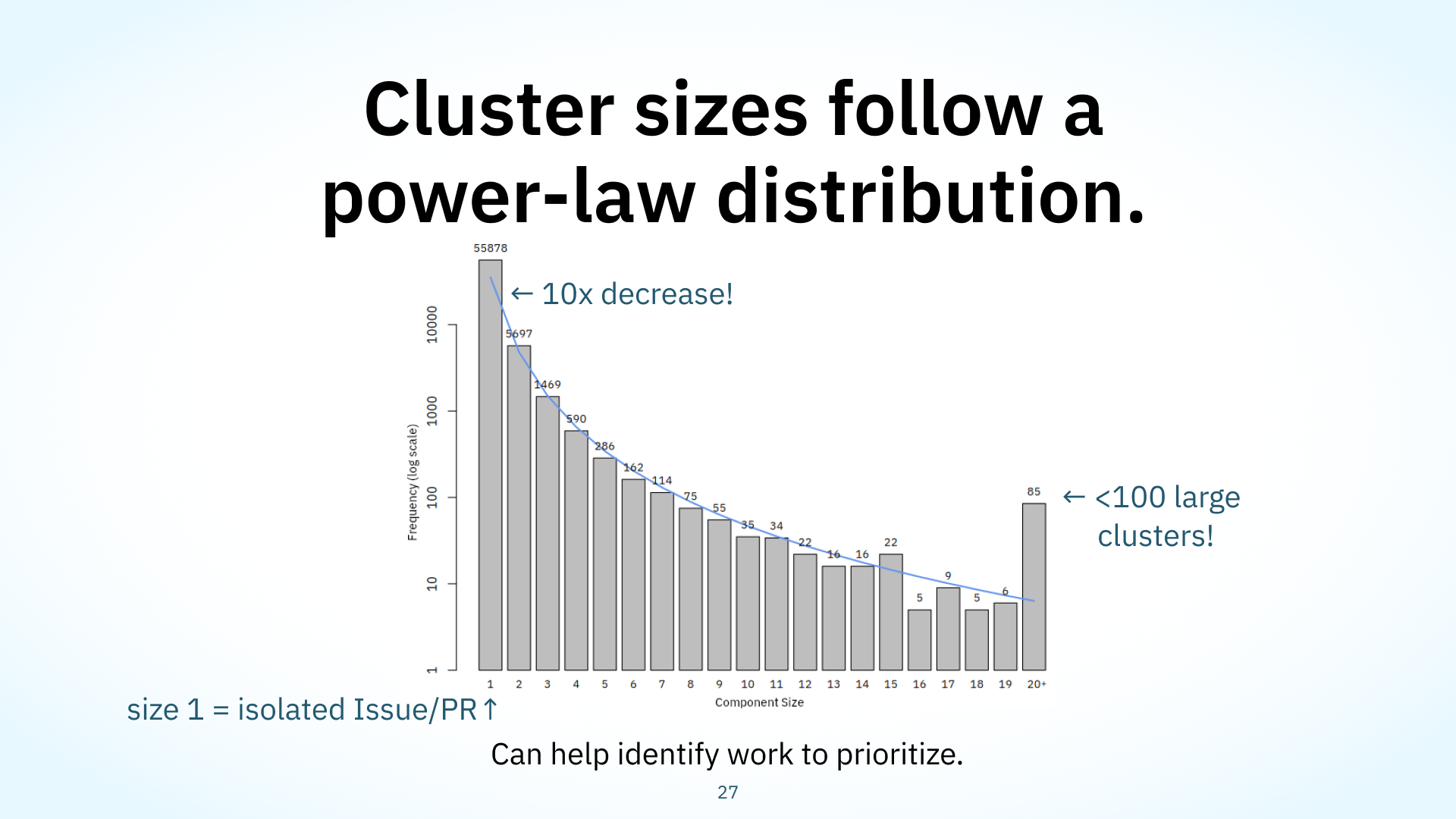

Let’s start with some characterization of the projects we studied. We found all the connected components, or clusters of connected issues or PRs, and measured their sizes and frequencies, which is shown in this bar chart. The x-axis here shows component size, and the y-axis show the number of clusters of that size on a log scale.

Cluster sizes are important, as they give us an immediate intuitive idea of how collaboration is normally structured: we can understand if people tend to build on previous work, making larger clusters of connected nodes, or if they create one-off PRs or Issues.

We found that cluster sizes followed a power law distribution, with many isolated nodes not connected to anything else and a few very large components with lots of nodes and interlinking. We found that there are ten times as many isolated nodes than 2-node components, which is unusual. You might think with how GitHub is structured around collaboration and documentation, there’d be a lot of PR to Issue links, or problem-solution pairs. Instead, we observed a lot of distinct problems or solutions that don’t apply to or aren’t linked to each other.

This power law distribution can help maintainers predict growth and appropriately allocate resources: power law distributions often indicate the presence of a few highly connected and influential hubs of nodes, so when we observe larger clusters starting to form, we can know, oh, okay, it’s likely that work and collaboration will continue to grow.

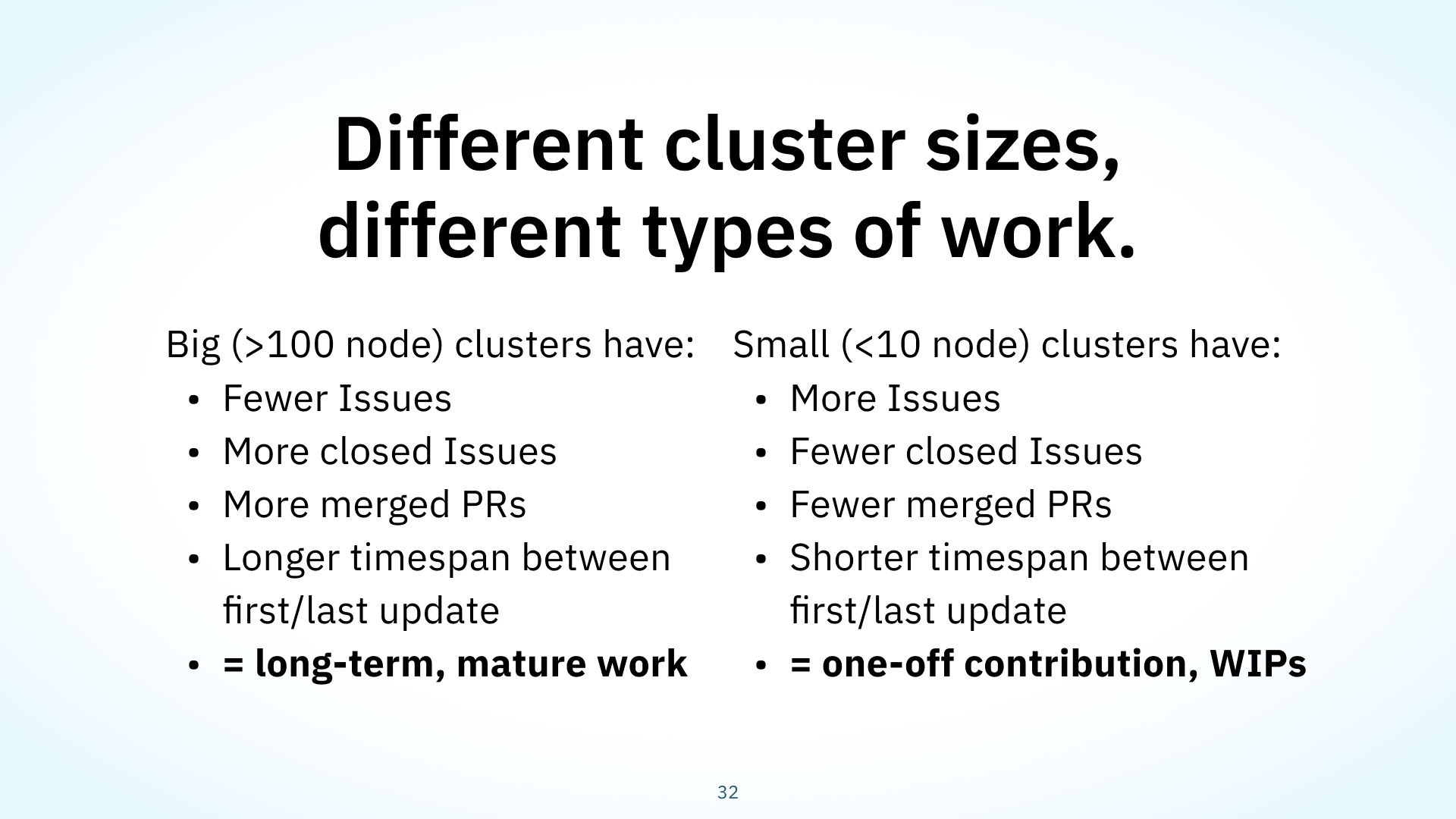

We also hypothesized that connected components of different sizes represented different types of work. We found that small clusters of nodes had more issues (shown in blue), which represents that they have more problems, fewer closed issues or merged PRs, so the work is left more unfinished, and a shorter duration between first and last update, indicating small clusters of nodes tend to represent isolated problems.

On the other hand, large connected components had fewer issues with more merged PRs and a longer duration. We might think of large connected components as more mature and active initiatives in a project, whereas isolated PRs or issues might represent one-off contributions.

Again, this can help with prioritization: larger clusters represent these critical areas where lots of high-impact collaboration is happening, so it’s worth taking a look to see how those issues are being managed. This is also useful for encouraging diverse contributions: developers new to open-source might just want to tackle a one-off issue, so smaller clusters or isolated issues might be a good place to start. On the other hand, developers looking to tackle a challenging core problem might want to start looking at the open issues in one of these large clusters or use them as reference documentation for past design decisions.

Workflow Type Definitions

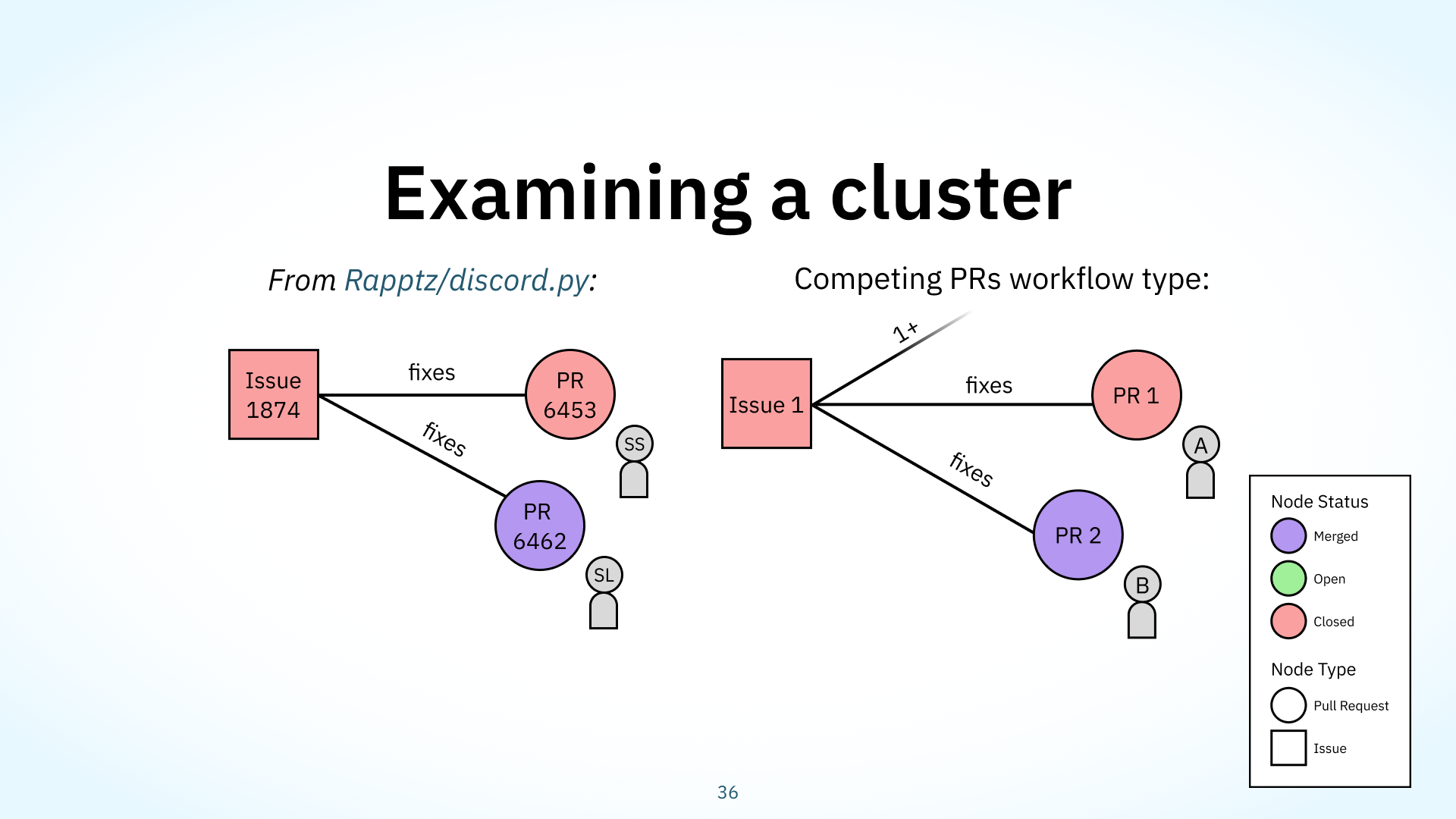

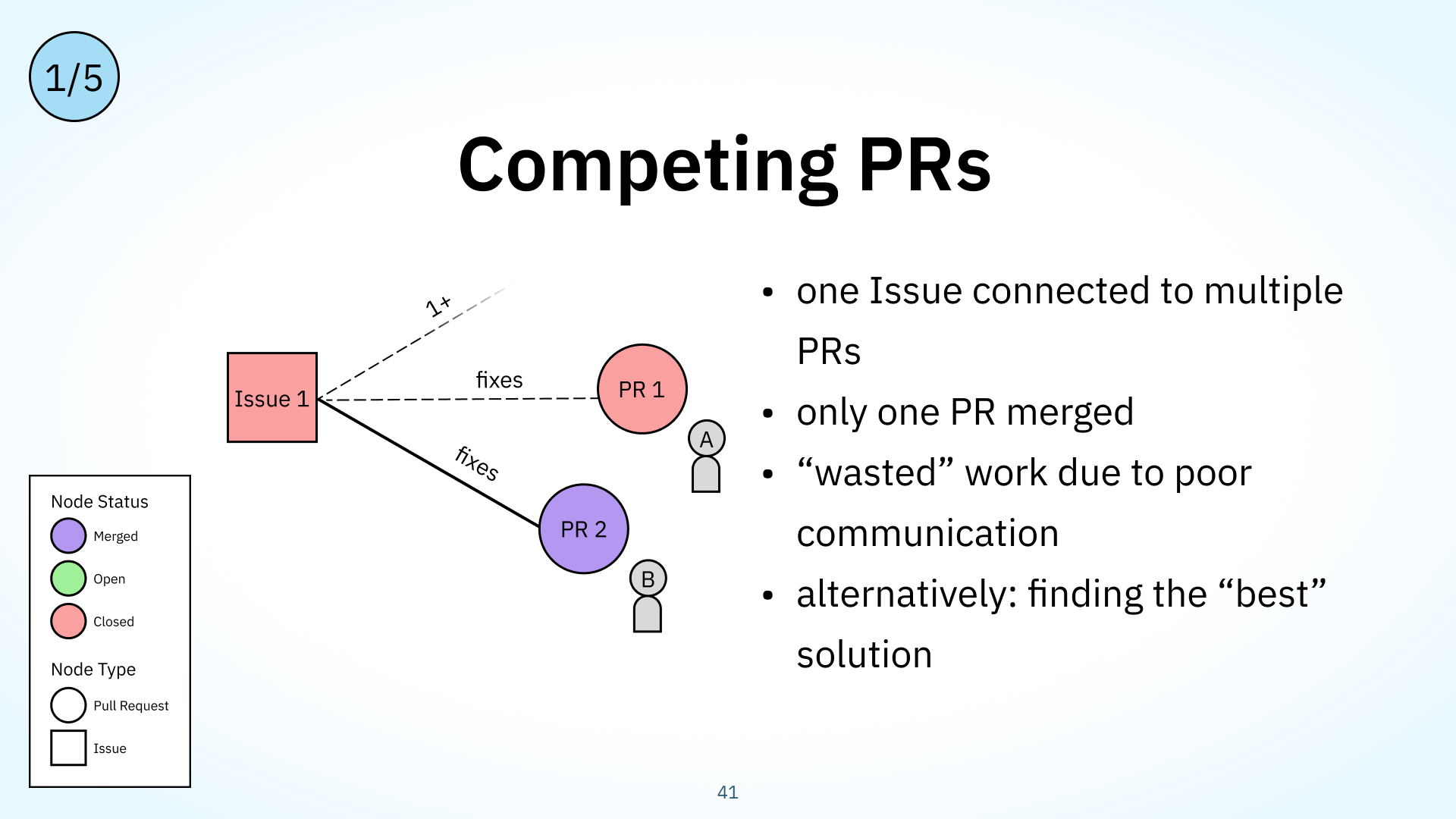

Next, I’ll cover the cornerstone of our work: our workflow type definitions. Let’s start by taking a look at one of these clusters of issues and PRs. Here’s an example from the discord.py project, a library used to build chatbots and other automations for the app Discord. Here, someone is requesting a feature — something to do with adding invoke_parent. Then, two folks have come along to create their own implementations of this feature. sudosnok on the left proposed an approach, but it was vetoed by the maintainer of the project. A few days later, SebbyLaw submits their own implementation, which is eventually merged. Note that both PRs reference the original issue with those “fixes” keywords I mentioned before: sudosnok used “closes”, and SebbyLaw uses “resolves”. Let’s visualize this as a graph. This is actually an example of one of our workflow types: the competing PRs workflow type. The competing PRs workflow type abstracts this example a bit by allowing for more competition, and more of these closed PRs.

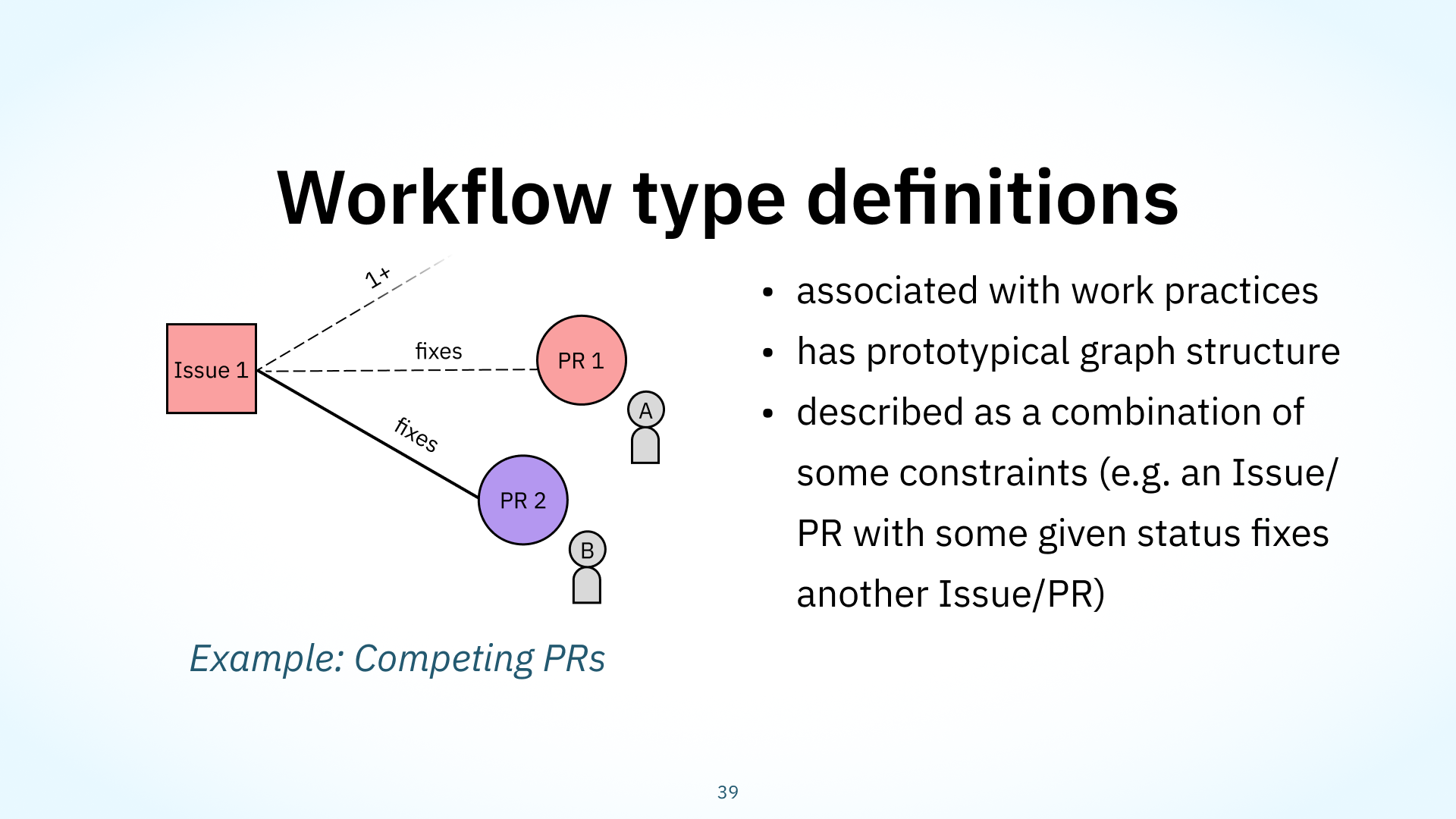

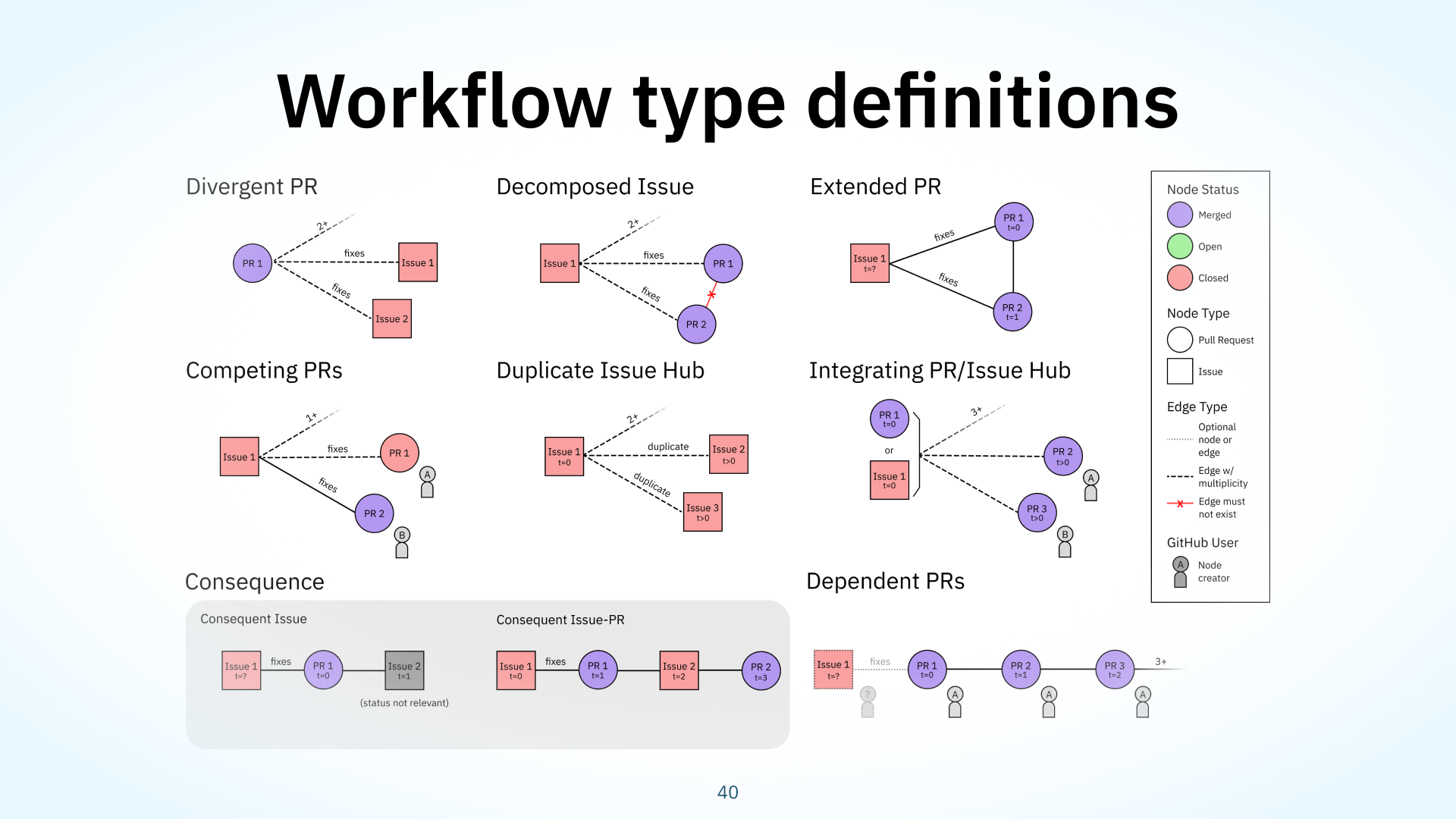

These workflow types are associated with work practices, like ‘breaking down complex work into small chunks’. Each workflow type also has a prototypical graph structure, as shown here. These graph structures were combinations of four types of metadata constraints: node type, status, authorship, and creation timestamps. We’ve defined nine prototypical examples of workflow types: I’ll go through a couple today.

Sometimes, contributors are eager to offer their own implementation of a task, and begin working on one while not communicating, which we observed in our competing PRs workflow type. The discord.py example I just showed earlier was one of these. It has a graph structure of a closed issue, this red square, connected to multiple PRs, with only one PR being merged, this purple circle. These PRs are created by different people, represented by the little people icons labelled A and B.

As in the discord example, you might have a feature request that multiple contributors start working on in parallel without ‘claiming’ the issue or otherwise communicating, and now you have multiple candidate implementations to review. Its associated work practice, or in this case, malpractice, has an implication that there was some wasted work due to poor communication, although competing PRs also allowed projects to be picky about what they merged. That discord.py example showed how the maintainer called out a performance implication in the first PR that they didn’t like.

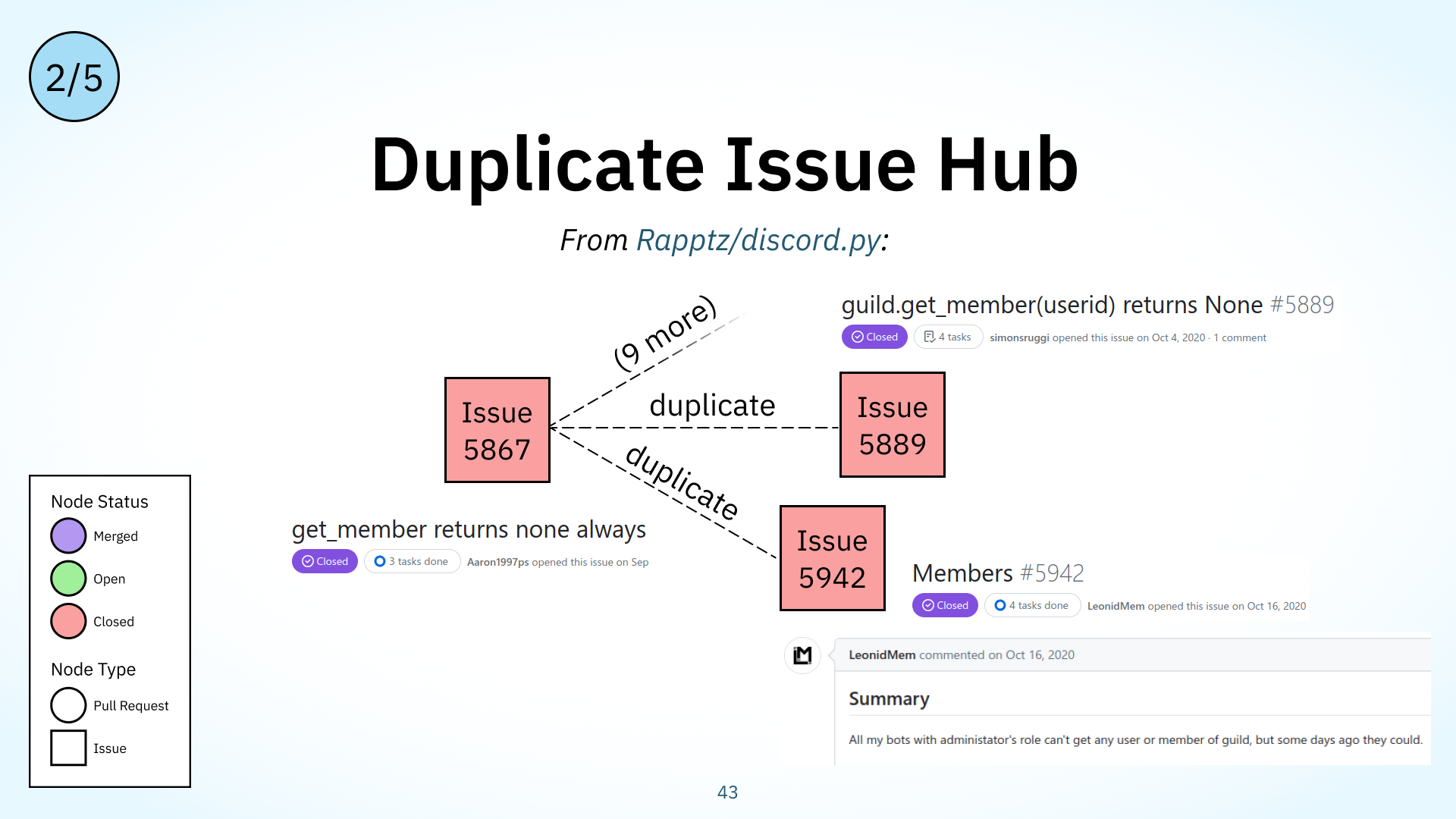

Another painfully familiar issue in open source is duplicate issues, where contributors report similar problems that are duplicates of previous discussions. Redirecting them to other, established discussions, takes valuable maintainer time. This is captured in our duplicate issue hub workflow type. Its structure consists of a issue, this leftmost red square, connected via ‘duplicate’ links to many other issues, the red squares on the right. The t=0 notation means that this hub issue, Issue 1, was created before the other duplicate issues on the right.

This happens if a bug goes out in a release, for example, many folks might report it at the same time without first searching through the other issues posted to GitHub, causing additional maintenance burden. Though this was one of the workflow types we first thought of and observed in our query refinement process, it turns out that duplicate hubs are actually rather infrequent. We observed only 15 instances of them, over all 90K nodes.

However, I’ll note that when issues are highly noticeable, as with breaking changes, these duplicate issue hubs can grow quite large. Here’s another example from the discord.py project: issue 5867 caused by a breaking change on the underlying app’s end was connected to 11 duplicate issues. When maintainers notice high-growth or large duplicate issue hubs, it’s worth considering how the change can be better communicated and made noticeable for users.

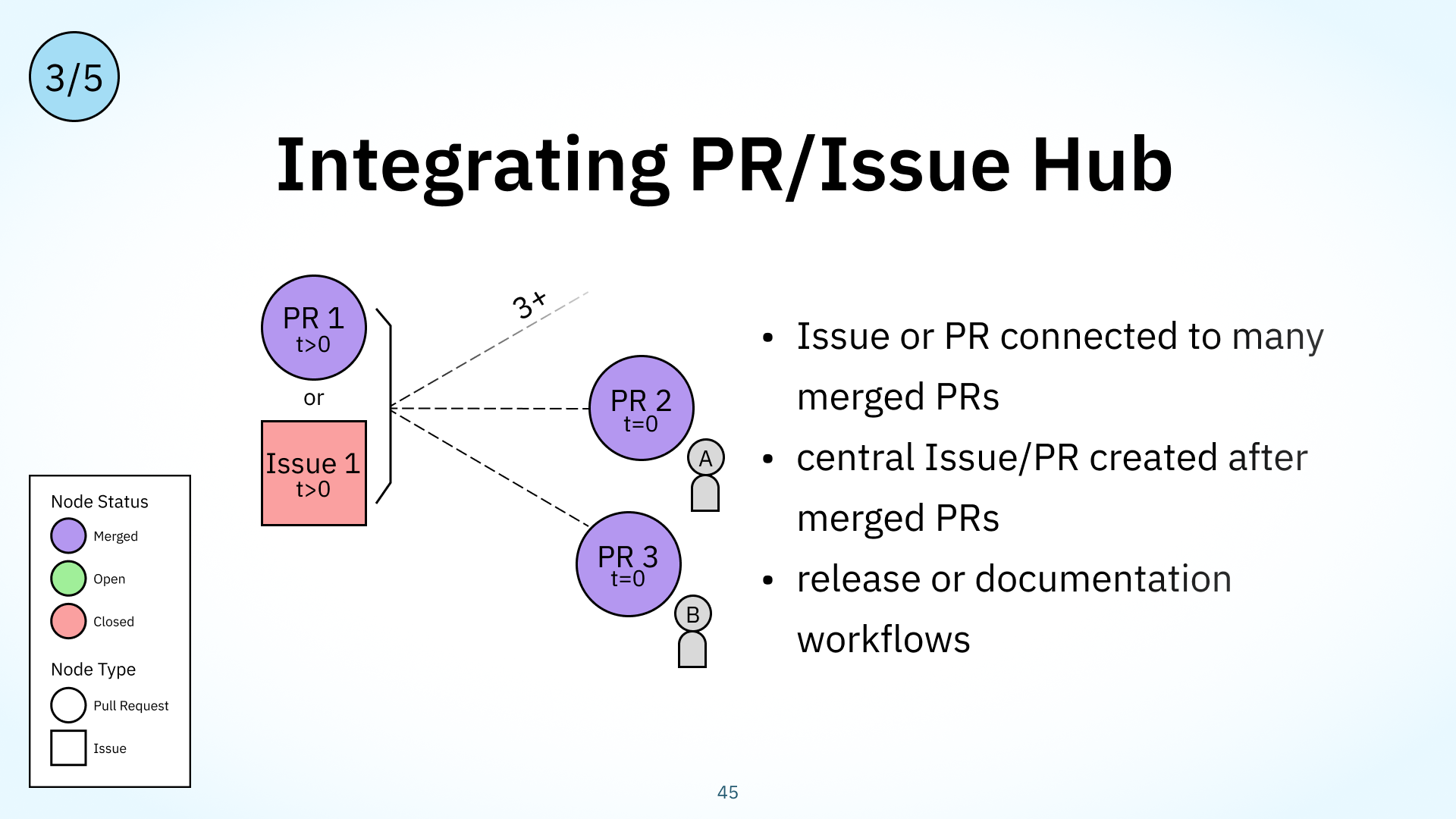

To perhaps combat some of the miscommunication that cause duplicate issue hubs, projects also tend to publish updates about recent work. Here’s an example from the apache/dubbo project, which employs a bot to create weekly Issues as a status report. It lists all the merged PRs from the last week. We observed this in our Integrating PR/Issue hub workflow type: its structure is a central PR or issue, as shown on the left, linked to many merged PRs, so those purple circles you see on the right.

The dubbo project used issues to collect reports, but some projects also use a PR: for example, listing all the PRs merged into the latest release candidate before merging that release candidate PR into the mainline branch.

This workflow type has a temporal constraint: the central PR tends to be created after the merged PRs. In practice, this typically models a release or documentation workflow, where maintainers aim to surface work after the fact so the community is more aware of what initiatives are occurring.

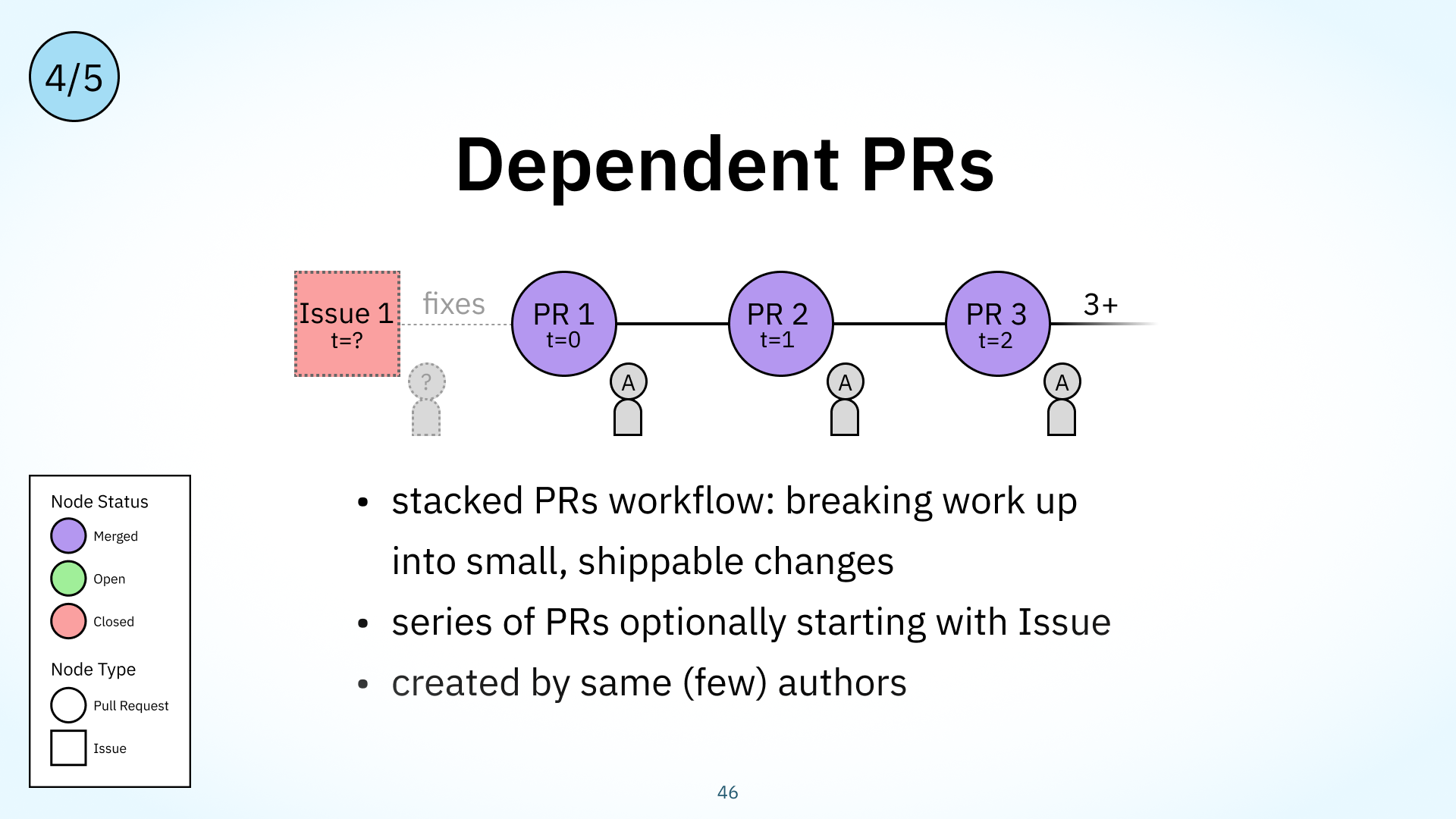

Stacked PRs and Graphite.dev are becoming more popular recently: if you’re not familiar with Stacked PRs, they’re a workflow for creating small, incremental PRs that build on each other and that facilitate code review and dev velocity. For example, I might make a small PR to update the backend, then a small PR to update the frontend, then a small PR to update the docs.

Our Dependent PRs workflow type models this type of workflow. Its graph structure is a series of PRs referencing one another in a chain, with a limited set of authors, usually just one. This workflow type is regarded as a good practice as it makes changes easier to understand and ship without blocking implementation work on a review.

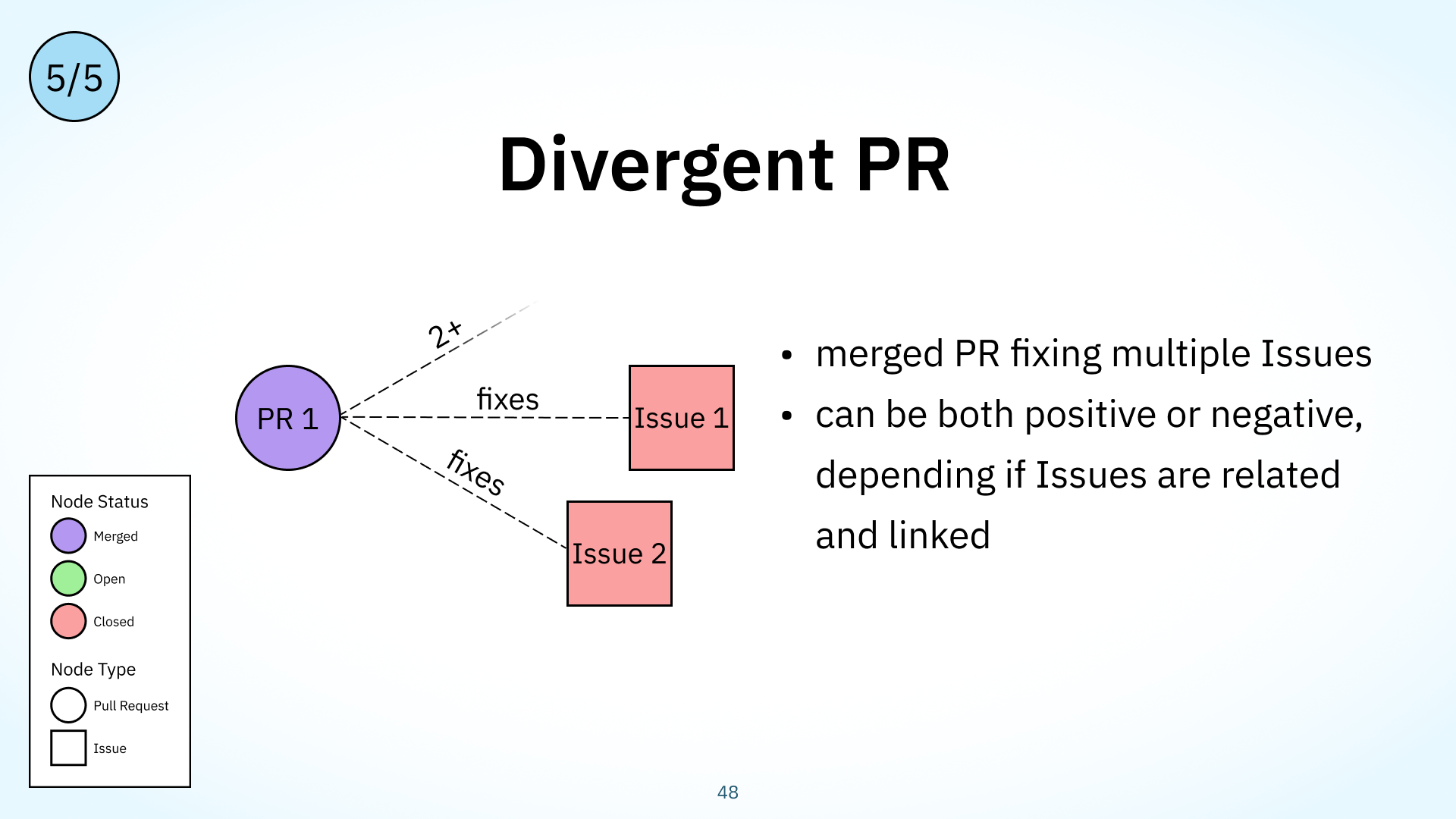

Finally, we found that developers tend to sometimes overdeliver in their PRs, addressing multiple issues at once. Here’s an example of a PR taken from the grpc-web project. A single PR fixes many issues that are, at first glance, unrelated. PRs like these will be more difficult to review and give feedback for, since the fixes are all mixed up in each other. This workflow is captured in our Divergent PR workflow type. It has the structure of a merged PR, this purple circle, that fixes several linked issues at once, these red squares.

This can be both positive, as when the linked issues are related or have the same underlying fix, or negative, as in the grpc-web example when the issues are unrelated. Again, negative divergent PRs violate the general principle of small, easily-understood PRs addressing a single issue.

Workflow Type Comparison

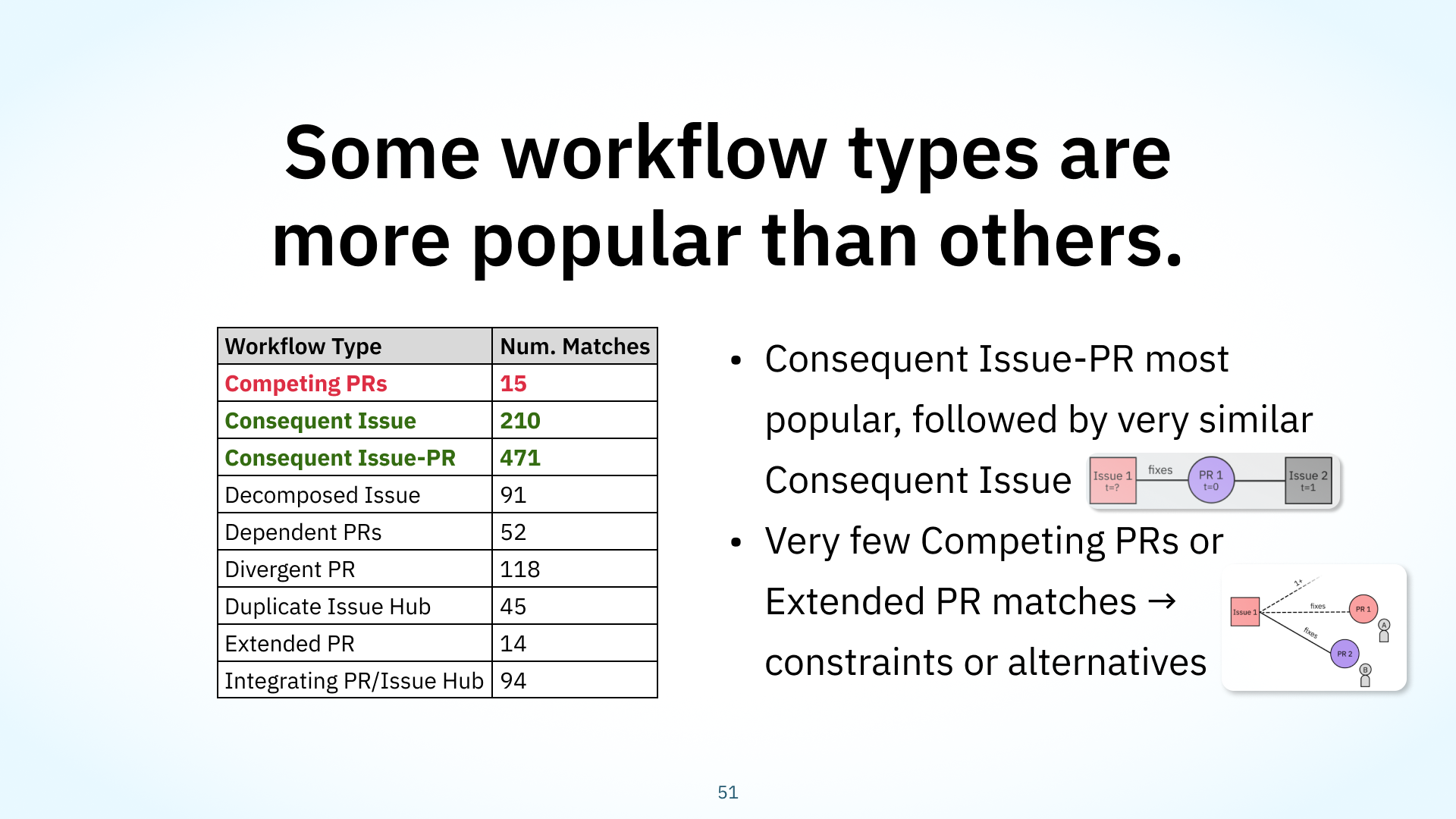

Let’s now talk about some ways these patterns compared to one another. We wanted to understand how frequently each workflow type arose in projects as it would explain the most common ways engineers work. We ran each of our queries across all 90K nodes, and counted up the number of matches from each workflow type. We found over a thousand matches of our workflow type definitions.

What’s more was that we found that these patterns weren’t evenly represented across projects: some workflow types were more frequently used, and we hypothesize that they’re more natural or embedded in software development culture. For example, the Consequent Issue-PR workflow type we identified was very popular : that’s an issue solved by a PR, which creates another issue. It represents the typical pull-based development model of Issue-PR well, so it wasn’t surprising that that was the most frequent workflow type. Another example: we didn’t see a lot of competing PRs, which implies that there’s usually limited wasted work.

This might be useful to keep in the back of your head as a benchmark: if your project has many more duplicate issue hubs or competing PRs than what we observed, that might be a sign to re-evaluate your issue reporting or code review workflows.

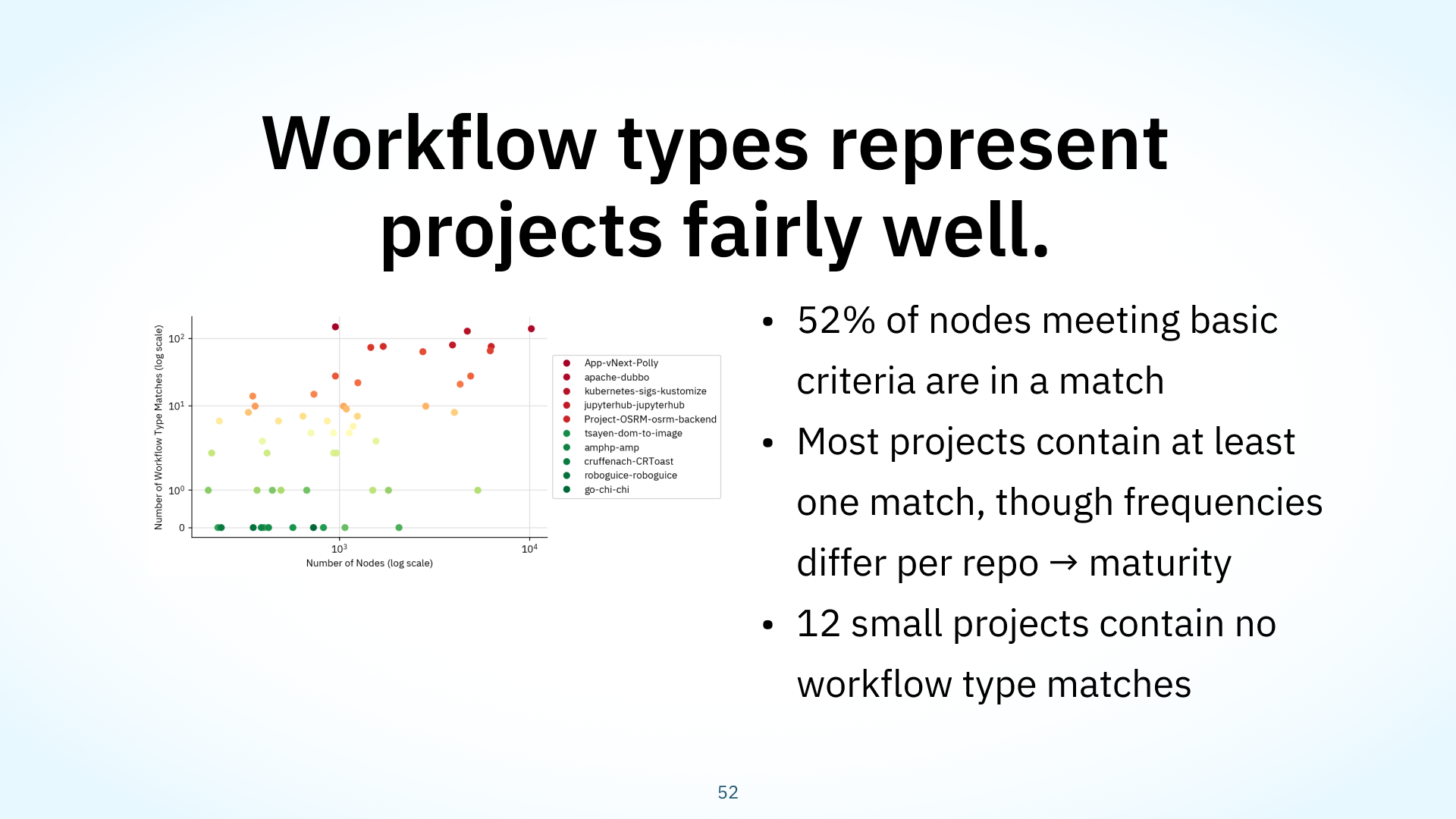

Finally, we observed that workflow types are fairly representative of the projects. 52% of all nodes that could have been in a workflow type – so, in a cluster with some other nodes and some links, were in a workflow type. Most projects contained at least one match, with larger projects tending to have more matches. This is a graph of the number of nodes in projects to the number of workflow types we observed in said project, with each dot representing a project, and you can see this general upwards correlation. You can see the largest projects, like App-vNext/Polly and Apache Dubbo, had the most workflow type matches, with about 150 matches each.

To us, this indicated that there’s some connection between project maturity leading to more organized collaboration and higher usage of these structured workflow types. This was consistent with the fact that the projects that used no workflow types, like roboguice or go-chi, were all relatively small, with only a couple hundred contributions. If your project has a very high number of workflow types, this represents that your project tends to have highly structured collaboration, which can be good.

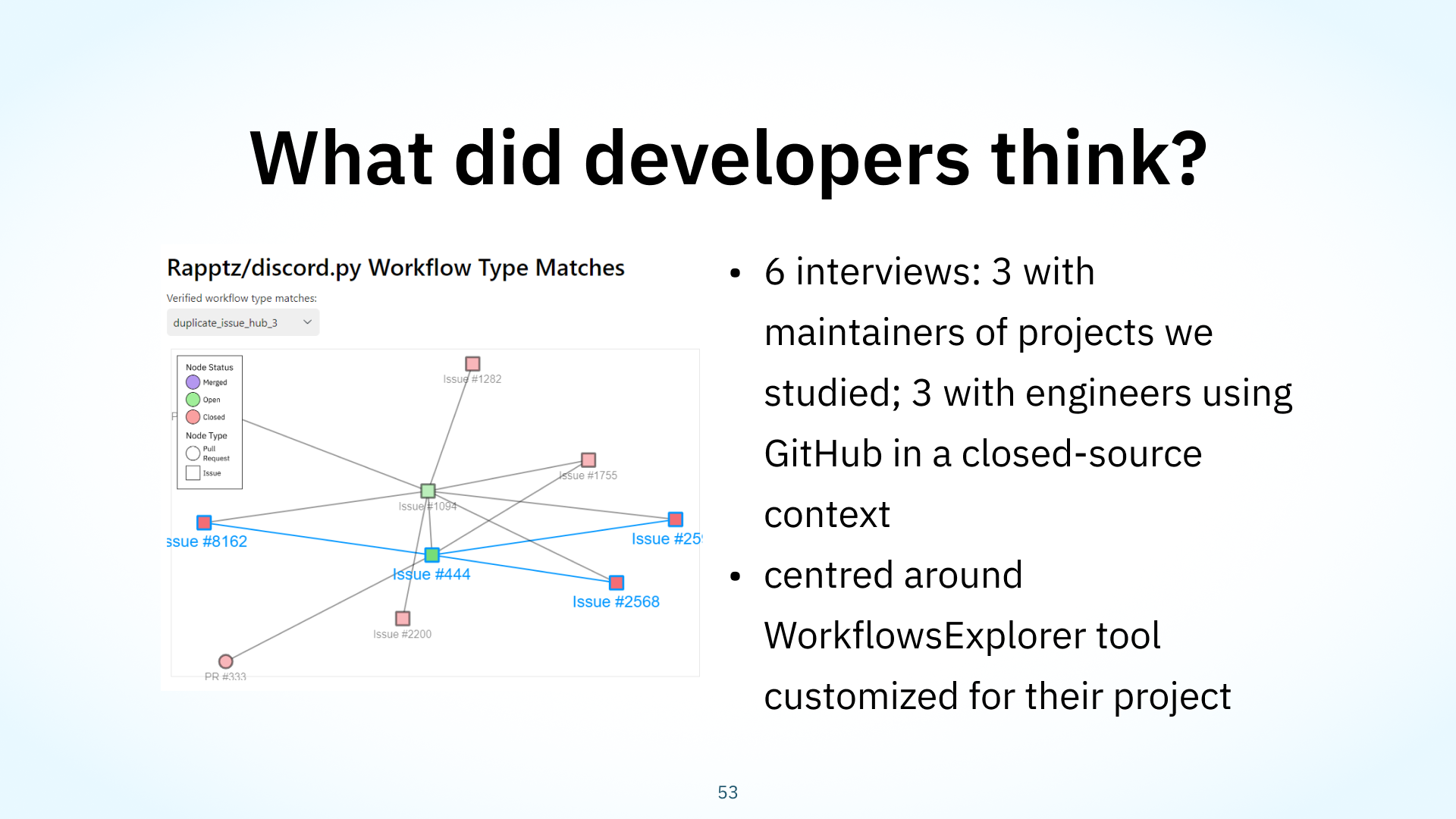

These were our takeaways from examining workflow type matches. But we were also curious what open source developers — you all — thought. We validated our definition and visualization tools with open-source developers in a series of six interviews. They focused on introducing developers to the interactive explorer tool preloaded with their project.

All developers agreed workflow types would help make better decisions on aspects of the development process. Some examples taken from our interviews: someone noted duplicate issue hubs might indicate a need for change in the documentation or bug reporting process, another person came up with the unique idea that workflow types can help prioritize and direct maintainership. If you see a competing PRs cluster, for example, but you see one of the PRs is part of a divergent PR cluster that resolves multiple issues, you might want to review that solution first. Our interviewees all noted that the visualization tools were useful for understanding inter-dependencies between features, providing valuable context that GitHub doesn’t.

Finally, some interviewees rightfully highlighted that workflow types are limited because they don’t examine the content of the issue, but we hope the visualization tool making even the initial surfacing of collaboration patterns easier is a first step.

Implications

Our work has wide-ranging implications. First, we’ve seen how examining the sizes of clusters of linked issues and PRs can demonstrate the type of work it contains. Because clusters tend to be either very small or grow to be very large, this can predict growth in certain areas of the project and in turn inform resource allocation and prioritization.

As well, we’ve seen that the visualizations of the graph perspectives can help navigate between initiatives and surface issues or PRs where additional effort is high impact, something our interviewed developers noted. The WorkflowsExplorer tool can be used to figure out which PR among a competing PRs workflow type is best to review, as I brought up before, and to visualize dependencies between features in development.

The tool can also help visually find problem areas in a project, where there are outsize numbers of competing PRs, duplicate issue hubs, or other forms of wasted work.

Hirao et al. argued that code review and duplicate issue identification tools can be improved by closer inspection of the links between nodes, among several other factors. Our approach does just that, and even extends it by analyzing multiple links within a cluster of nodes. Another implication of our graph perspective is that it’ll allow us to further improve these tools: we can use our insights on cluster sizes to improve good-first-issue detection.

But the biggest next step for our work is talking more with developers like you. I’ve already spoken about some of the developer interviews we’ve conducted, but if you’d like to work with us on understanding the collaboration patterns in your project, please get in touch or find me after this talk!

Talk Conclusion

Today, I’ve covered our novel graph-based perspective and our ideas for the workflow types definitions. The core plus of our approach is that it can be easily automated, making it easier for maintainers to identify and curb unwanted types of collaboration. As well, I’ve highlighted some insights that this graph perspective has revealed and how we can make use of them to steer your communities in a better direction. Think of this PR-Issue graph as a Grafana dashboard that lets you monitor your project’s collaboration health: it acts as a global point of reference for understanding your project as a whole and can give you early alerts when things might be going south. Again, reach out if you’d like to work together with us!

Thank you so much to the Linux Foundation for organizing the conference and making my first speaking experience such a memorable one. I thoroughly enjoyed the conference and am looking forward to speaking at others in the future — it’s one of my goals for 2024!

Keep an eye out for the next post in this series where I’ll cover more about the day-of experience, my hectic scheduling that I somehow pulled off, and lessons learned both from speaking and attending.

-

The conference was smack in the middle of my first few finals — I even had to beg a professor to reschedule my first one — and I needed to rush back to Vancouver after my talk to make my second exam, so I was only able to stick around for one day. ↩︎